The year 2025 in Kashmir left like any other year in Kashmir: full of rumours, expectations and disappointments. What kept Kashmiris going was their knack for good humour, their love for wazwan and their witty capability to dismiss. But 2025 was also a year of quiet literary resilience. Bookstores opened and closed like the shutters on Residency Road, depending on the day’s mood, yet the love of reading stayed stubborn.

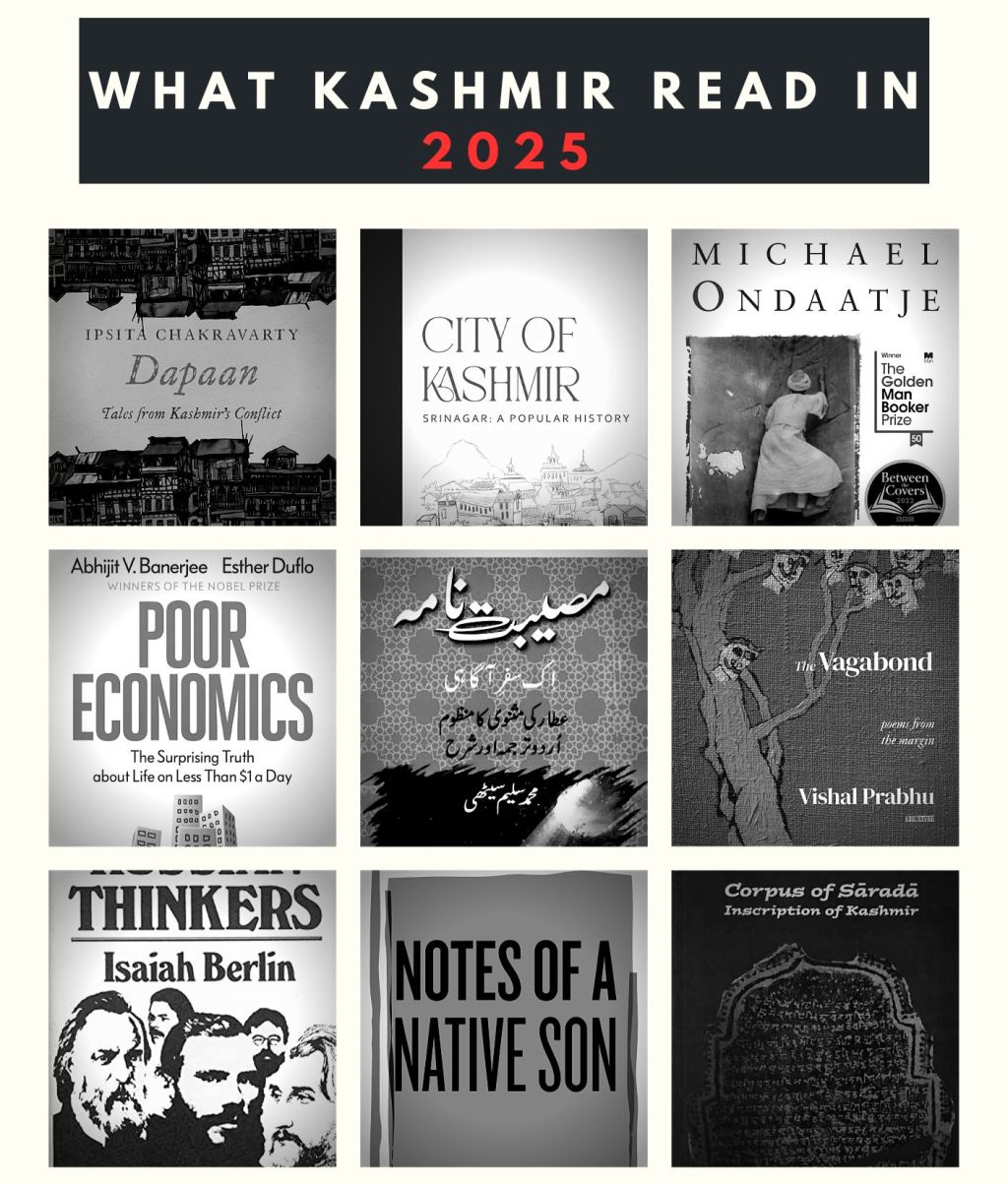

Here is a list of best reads from some of the Kashmiris in 2025 along with their brief introductions to the books. This compilation isn’t just about the “best” books; it’s about the books that travelled from hand to hand, WhatsApp group to WhatsApp group, and encounter to encounter in a place where literature remains when everything else being on survival mode.

Parvez Bukhari (Journalist)

For Now It Is Night – a selection of stories by Hari Krishna Kaul

Outside of my precious little personal and professional universe, reading is the primary half of my life. Everything else forms the other half. As always, reading to understand the times we live in has been a constant in 2025 too. But as is often the case, the severe urge to afford a peep into our own past is a hook that never stops pulling. Although it was published a couple of years earlier, For Now It Is Night – a selection of stories by Hari Krishna Kaul kept swimming in my mindscape this year. The stories, originally written in Kashmiri language – and very masterfully translated into English – are rich in style that is sensitive on the leash, full of wit, humor, often dark. And, above all these vignettes offer a very nuanced perspective of the contemporary Kashmiri society.

A society and culture that have transformed during the last four decades perhaps in more ways than during the last few centuries leading up to our times. The insights Kaul brings to his writing can make you laugh and break your heart at the same time. But it also leaves behind an uneasy feeling, somewhat like a spark that flies in the darkness. Treat yourself to it, if you haven’t already.

Mirza Waheed (Novelist)

Heaven Looks Like Us– a collection of Palestinian poetry edited by George Abraham and Noor Hindi.

There are too many ‘best books’ to choose from, really, but if I’m forced to pick one, it would have to be Heaven Looks Like Us, a landmark collection of Palestinian poetry edited by George Abraham and Noor Hindi. It is an extraordinary book of poetry that includes work from some of the most important, critically-acclaimed, intergenerational Palestinian poets such as Najwan Darwish, Hala Alyan, Fady Joudah, Suheir Hammad, Dalia Taha, Nathalie Handal, Jehan Bseiso, Mohammed el-Kurd, Mourid Barghouti, Mosab Abu Toha, Refat Alareer, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Mahmoud Darwish, among others.

This is poetry of exile, grief, love, home and land, and equally, it’s a defiant, collective song against dispossession, erasure and violence. It is also, in both its deep shattering sorrow and relentless beauty, a reclamation of the Palestinian self that no colonial and imperial enterprise can extinguish.

George Abraham and Noor Hindi’s introduction serves as an illuminating guide to its poetics and a profound call to action for “fostering greater inter-connectivity in and beyond [our] global writing community…” They write: “Here, poetry gives us the miracle of language activated beyond witness and into with-ness,” and “We sing like the whole world is at stake. We sing because the whole world is at stake.”

Everyone should read this beautiful, necessary book. Every library should give it a home.

Gowhar Geelani (Author, Journalist)

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin.

When one thinks of the civil rights movement of the 1960s in the United States, segregation, racism, and discrimination against Black Americans, we often reflect on the body of work and struggle by Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. [I Have a Dream speech], but one can’t ignore James Baldwin.

A fabulous writer with a great sense of history and humour, and sensitivity as a writer, Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son comprises a random collection of stories about his growing up as a preacher’s kid, racial profiling, and many anecdotes about the unimaginable suffering of Black Americans.

The book also contains his travel experiences, especially to Europe. You’ll also get to know about the ordeal of the intellectuals who wrote or summoned the courage to speak out against the oppression faced by Black Americans. Some of the intellectuals had fled to various parts of Europe from the 1920s to the 1940s.

The author’s evocative prose, distinct style of writing and eloquence make it a riveting read. Baldwin’s passion is clear from his writing — how strongly he felt about the subject and how he desired to change, for good, the lives of the Black American community. This non-fiction work by Baldwin was originally published in 1955.

Baldwin’s integrity as a writer can be felt and found in sentences like these:

“I love America more than any other country in the world, and exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Suhail Naqshbandhi (Multidisciplinary artist, Editorial cartoonist, Comics creator, Watercolorist and Designer)

Stories by Akhtar Mohiuddin

His stories stay with you because of the images they create—quiet, vivid, and often unsettling in the way Chekhov’s are. From the first few lines, your curiosity is already at work, and it never really lets go. There are no dead patches. The emotional layers unfold slowly, without announcement, and that restraint is exactly what makes him such a strong storyteller. There is wit too, and sometimes humour, but never loud or showy—just enough to catch you off guard.

That he is a major figure in Kashmiri literature is not in question. What is disturbing is how poorly we have cared for his legacy. Finding his books was a struggle. None of the well-known bookstores here had even one of his titles. This is work that should be taught in schools, read early, returned to often. At the very least, it should be easy to find.

I saw him only once, at the inaugural meeting of the Cancer Society of Kashmir. After the opening remarks, people were asked to introduce themselves. Most of the audience consisted of doctors, so the introductions became a steady roll call—Doctor so-and-so, Doctor this, Doctor that. When Akhtar sahab’s turn came, he paused briefly and said, “Akhtar Mohiuddin. A patient.”

That single line told you almost everything about the man.

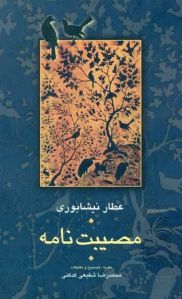

Prof. Mufti Mudasir Farooqi (Professor and Comparative studies scholar)

Musibat Nama by Farid-ud-Din Attar.

It is probably the finest poetic treatment of the problem of suffering: witty, humorous and yet profound.

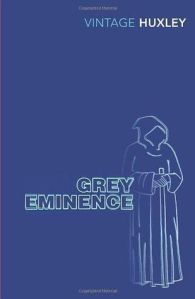

Hakeem Sameer Hamadani (Architect, Conservationist, Architectural historian, Author)

Grey Eminence by Aldous Huxley.

For some reason, rather than reading anything ‘new’, I have been revisiting books and authors, some of whom I had last read in my college days. Favourite, I would say, definitely Grey Eminence. The first time I read this historical fiction by Huxley was sometime after I had finished my architectural studies. I liked it then, and today more than a decade later, I can say I love it.

Part of the attraction is this temptation to attempt something similar: a historical novel. Yet the deeper pull is the book itself.

Huxley’s devastating portrait of how power devours everything it touches. The book is an intimate study of a Capuchin friar, Father Joseph, who began as a genuine mystic, an ascetic who shunned material wealth and comfort, founded convents, wrote spiritual poetry. This man might have died a saint. Instead, he became, if not the architect, at least a Machiavellian agent for a war that left devastation and death everywhere — all in the serene conviction that he was doing God’s work. I am sure readers will find parallels in our own societies, both in the past and today.

Amir Suhail Wani (Engineer, Author, Columnist)

Russian Thinkers by Isaiah Berlin.

The book is a rare mixture of history, philosophy and the evolution of literary thought in Russia. We usually ignore Russia and its rich philosophical and literary legacy, neglecting the fact that till recent times it was a continent packed into a country.

This book cures the deficiency of ignorance of Russian thought and the romance of life and literature as it unfolded in the erstwhile USSR. The book is a must-read for any student interested in understanding the development of ideas and the interplay of politics, literature and philosophy.

Huzaifa Pandit (Academician, Poet)

The Vagabond by Vishal Prabhu.

Reading it puts one in the mind of Emily Dickinson. It adopts a similar playful approach to the form to test the possibilities of language and interpretation. The poems are fleeting tissues of a flâneur gaze that seeks a redefining of meaning, coherence and belongingness in a world where such vocabulary is under sustained erasure. An undercurrent of re-exploring and redrawing the anxiety and tension between experience and expression, truth and testimony lends the collection a compelling unease that unsettles and rivets in equal measure.

Overall, The Vagabond emerges as a finely sculpted book where the age-old question of form and its relationship to content finds new and poignant expression in this “catalogue of lived realities.”

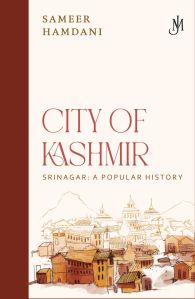

Khawar Khan Achakzai (Cardiologist, Columnist, Book critic)

City of Kashmir: A Popular History of Srinagar by Sameer Hamdani.

In the modern works on Kashmir, which are largely driven by the geopolitics of competing nations, Srinagar possesses a thin and almost perfunctory political history; a marginal outpost in the larger ideological currents of the subcontinent. However, the book City of Kashmir: A Popular History of Srinagar by Sameer Hamdani deconstructs this notion and relocates Kashmir as a densely animated political polis among the cities and cultures of the medieval world: a site of mobilisation, contestation and ideology production.

It explores Srinagar at a scale never attempted before and dwells on archival material that had been completely unknown until now, anchoring the text into a rare historical depth. The academic cohesion has an emotional cadence of a layered personal narrative. It is suffused with an element of storytelling and sounds as if an almost hidden tale is being told, evoking the emotional life of the old city without collapsing into romanticisation.

Jehangir Ali (Journalist)

Paradise by Abdulrazak Gurnah.

A poetic tribute to human resilience, memory and survival under an imminent European takeover ahead of the World War I, Paradise, which is set in the colonial East Africa, delves into the themes of identity, colonialism, love and the tough realities of life masked by beautiful landscapes which contrast earthly suffering with the religious ideals of paradise.

With a dream-like narrative, the novel follows Yusuf, a young African boy who is taken as a servant by a merchant to collect Yusuf’s father’s debt. The 12-year-old boy endures a string of hardships in a hostile world on the brink of change and in the process loses the innocence of his childhood.

Junaid Ahanger (Medical doctor, Poet)

The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje

My best read in 2025 by quite a stretch was the Booker Prize-winning magnum opus by Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient. To me personally, this novel is the pinnacle of literary achievement and the greatest contemporary work of fiction. I read it once when I was a young boy and was swept in by the mesmerising lyrical landscape it provided, of earth and beyond. And this year when I revisited it (as happens with many a classic), I experienced the magnificent transcendence that the novel possesses.

Truly beyond time and space, I ended up writing an editorial about the book called The Covenant of Melancholy, and I am sharing a portion of it here:

“All I ever wanted was a world without maps,” writes Michael Ondaatje in his intimate meditation on the human condition. In his magnum opus, The English Patient, Ondaatje wrote in a language that outstripped and far outreached our notion of the spoken word. What might read as an innocuous line at first glance, the measure of its profundity can only truly be felt after having read through the entire book.

The written word, stripped of all superfluous weight, carrying the weight of only the world it inhabits. This ancient art, through the ages in its multitude of forms — poetry, prose and beyond — truly hits home when it has that supremely tantalising quality of restraint, of what is said and more importantly what is not. Fulfilment and its lack, leaving the reader on the cusp of a private inquest. A tentative submission to the senses in giving shape to the seemingly vacant, in breathing form into that void. Steady cadence, moving epilogues, stirring prologues, stem-winding rhymes that offer us at times an escape from barren days like clockwork, and other times hold a candle in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, reminding us, and the world at large around us, that perhaps the idyll we always aspire for is within us, in this desire to be heard and felt.

Mehak Jamal (Film Maker, Author)

Dapaan by Ipsita Chakravarty.

As histories are rewritten, archives deleted, books banned — oral histories and memory-keeping grow ever more vital. The book reminds us that as long as we keep telling and retelling our own stories, erasure of what has happened in Kashmir becomes harder. The act of remembering becomes both defiance and survival.

In a land where official narratives try to overwrite lived truth, every retelling — be it in whispers, initials, or coded performances — is an assertion of presence, of existing. In the end, Dapaan is not just a book about Kashmir’s conflict — it is a testament to the stubborn endurance of memory.

Shakir Mir: (Journalist, Book Critic)

Corpus of Sharada Inscriptions of Kashmir by B. K. Kaul Deambi.

Until I had read the Corpus of Sharada Inscriptions of Kashmir by scholar B. K. Kaul Deambi, I was not aware that the earliest inscription written in the Sharada script is to be found, not in Kashmir, but in Attock, modern-day Pakistan.

Deambi’s book is a powerful repository of historical anecdotes and observations that speaks of the author’s incredible flair with his discipline. It is the kind of book that will reward the historians working on Kashmir for generations to come. Although cited in numerous modern works, the monograph is still, in my opinion, one of the most under-appreciated explorations into the material culture of the Valley.

The most beautiful aspect about the book is Dr Deambi’s scholarly rigour and his non-partisan character, not least because when Deambi wrote Corpus, the literary scene in Kashmir was flooded with titles betokening personal or political bias.

The book taught me a lot about the syncretic nature of Kashmir’s history. For instance, Deambi particularly notes how the Sharada language reached its literary apogee in the 15th and 16th centuries. That’s the period when Kashmir was ruled under Muslim sultans.

In modern-day history-telling, Sharada is impulsively associated with the Brahmanical religious order in Kashmir, and the fact that the language has heavily been patronised by the Muslim rulers of the region is often neglected.

Deambi, however, acknowledges it with a remarkable poise. As he does the similar syncretism experienced during the Hindu period when Buddhism flourished symbiotically with, and alongside, Brahmanism.

He writes about verses inscribed on a stone at Parepur village in Kashmir that mention the name of Sultan Hassan Shah (r. 1472–1484 AD). Another Sharada epigraph carved on a stone in Kothiher village in Anantnag hails Sultan Shihabuddin (r. 1354–1373 AD) as a great king whose valour scares away “the enemies… to remote corners… as if pursued by a mad elephant.”

The praise for the sultan in the verse is longer than the dedicatory prayers for Lord Ganesha and Lord Shiva.

Another inscription etched on the walls of a 14th-century hermitage in Khonmoh in South Kashmir introduces Sultan Sikandar (r. 1389 to 1413 AD) with effusive praises, calling him an “illustrious” king.

The author also writes about a Sharada inscription in Digom village in Shopian dating back to the Afghan rule in which a person is attested to have consecrated a spring as a religious donation to a Pandit. This means that even under Afghan rule, which lasted until the early 19th century, Sharada continued to be a major script patronised by the Valley’s non-Brahmanical rulers.

Ejaz Ayoub (Economist)

Poor Economics by Abhijit V. Banerjee & Esther Duflo.

This book looks at poverty as it exists in the real world and the practical ways we can try to reduce it. Using insights from controlled trials, the authors get into how the poor actually make everyday economic decisions. Through this lens, they show why many well-intentioned policies don’t work the way they’re supposed to.

The book is filled with real stories and experiences, that feel genuinely connected to reality rather than reading like just another economics textbook.

Iqra Rasheed Shah (Psychiatrist)

Dozakhnama by Rabishankar Bal

A melacholic and dark afterlife conversation between two men from two eras: Ghalib and Manto. Dozakhnama translates to “conversations in hell” and this was my second time reading them.

Set in a liminal space between hell, memory, and history, the book becomes less a biographical exercise and more a philosophical inquiry into the moral burden of witnessing one’s times.

Ahmad Parvez (Musician)

The Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov

I didn’t read The Physics of Sorrow in a straight line. I moved through it slowly, in fragments, the way memory actually works. Georgi Gospodinov doesn’t try to explain sorrow. He treats it like something that already exists, something that moves from one life to another.

The Minotaur in this book is not a monster. He is someone born into a situation he did not choose. Trapped, misunderstood, punished for simply existing! That felt familiar. Some people are born into peaceful stories. Others are born into unfinished ones. In places like Kashmir, sorrow is not personal at first. It is inherited.

The voice of the book is unstable. The narrator moves between lives, decades, and bodies. This is not a trick. It is a refusal to claim pain as property. At a time when suffering is constantly performed and compared, this book does the opposite. It spreads sorrow out. It makes it collective, ordinary, and therefore more honest.

The book is made of short sections, lists, and broken memories. That is how history actually enters our lives-not as one big event, but as interruptions. Family stories change. Childhood memories become political later. Silence fills the gaps. This felt deeply familiar to me.

There is humour in the book, but it is quiet. It never tries to make things lighter. It comes from endurance, not escape. Gospodinov understands that long sorrow teaches discipline. You stop asking for meaning. You learn how to carry it.

The Physics of Sorrow does not offer healing or closure. It does not pretend that everything can be resolved. It simply says: you are not alone in this feeling. Others have lived with it too.

I didn’t finish the book feeling better. I finished it feeling less isolated. For those of us who come from places where history enters the home without asking, that kind of recognition is enough

Khalid Wasim Hassan (Academician, Researcher, Columnist)

The Psychic Lives of Statues: Reckoning with the Rubble of Empire by Rahul Rao

Being witness to youth-led, socio-political movements that aimed to destroy the state symbols and statues in many parts of the world made me curious about the correlation of these acts to the notion of ‘decolonization’ in the contemporary postcolonial world, and I am happy that this brilliant work of Rahul Rao on The Psychic Lives of Statues helps me to sort this relationship.

For a researcher like me, who focuses on public spaces in conflict zones, the book offers a fresh perspective on how societies reinterpret their past and present through public iconography. Glancing over the first few pages, the book caught my attention by bringing back the memory of the brutal death of George Floyd, who was suffocated to death by a policeman in the United States, and the movement of ‘Black Lives Matter’ against the extrajudicial execution of Black people. Throughout the book, the author takes us across South Africa, England, the United States, and even India to showcase the statues as sites of resistance and contestation. By citing examples of both the toppling of colonial statues and the raising of new ones, the author demonstrates that the statues remain powerful vehicles for representation and cultural memory. While examining the history of iconoclasm, Rahul Rao compares past movements with contemporary ones. Statues in the past were seen as symbols of the ruling regimes; therefore, movements that destroyed those statues announced the end of a regime. In contrast, as emphasised by Rahul Rao, the present anti-statist movements are not celebrating the demise of a regime; rather, they aim to decolonise political thought and alter the distribution of power in society. Last but not least, the book will contribute to scholarship on South Asian politics, where the statues, while serving as assertions of caste, class, and religious identity, become sites of contestation. Historically, the Dalit movement in India was successful in building statues of Dr B.R. Ambedkar to announce a struggle against caste hierarchy, while the Hindu right-wing is trying to popularise the politics of Hindutva through the tall statues of their ‘ideological’ heroes.

Insha Qayoom Shah (Academician, Poet)

Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson

It is a romantic narrative, characteristic of Ms. Winterson’s oeuvre. It is a contemplation on affection and yearning and concerns the notion that love may endure regardless of the circumstances. It is a profound exploration of an exceptional fervour and the depths of unreciprocated affection. It pertains to the body – each individual part, every pore of the skin, and every surface that the beloved contacts. The narrative is delivered by an unnamed and gender-neutral entity regarding its affection for a married woman named Louise.

The novel discusses their affair, love, desire, and the betrayal of the body. Winterson’s prose transcends the realm of magic. She understands precisely which nerve to stimulate, which emotion to convey, and which vulnerability to depict, prompting the reader to reflect on their own existence. She discusses the intimate familiarity partners have with each other’s bodies. How they are acquainted with every scar, every detail, every birthmark, and every crevice of the body, and how love penetrates those areas. The novel features an unconventional narrative; but, after you acclimatise to it, you will find it irresistible. The prose exemplifies lyricism at its finest. Winterson’s depictions and intricacies of love and lovers are vital. The book is astute; nonetheless, it mostly explores the essence of love and our perseverance for the beloved, even in the face of inevitable failure.

Zabeeha (Housewife)

The world with its mouth open by Zahid Rafiq.

Zahid Rafiq’s book arrives as one of the most quietly devastating works to emerge from contemporary Kashmiri writing. What distinguishes it is not simply its political acuity or its ethnographic sensitivity, but the way it marries the two with a prose style that is at once economical and emotionally resonant. Rafiq writes with the discipline of a reporter and the interiority of a novelist; the result is a narrative that feels lived rather than observed, and witnessed rather than merely recorded.

At the centre of this melancholic book is a Kashmir that rarely enters mainstream discourse: a Kashmir of ordinary labour, of domestic fragility, of people caught in the slow violence of uncertainty. This book reads like Russian literature.

Mohammad Ayaan (Class 12th Student, Burn Hall School)

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

It is a reflective, deeply personal journal where the Roman emperor captures the core of Stoic philosophy, focusing on self-discipline, accepting what cannot be controlled, and maintaining inner peace amid struggles.

Rather than telling a story, the book offers calm, practical reminders about staying humble, being kind, and keeping emotions in check. Its simplicity and honesty make it timeless, giving modern readers clear guidance on how to think, act, and stay grounded in a chaotic world.

Naveed (Banker)

Loal Kashmir by Mehak Jamal

I am not a very seasoned reader of non-fiction and this book was just my 3rd book on Kashmir. Jamal writes without melodrama, allowing the rhythms of fractured Kashmiri life to surface through small, intimate moments that carry the weight of a prolonged conflict.

The book resists easy politics and instead dwells on what conflict does to memory, language, and desire, especially for the young. The book has some amazing stories which feel beyond reality.

Leave a reply to Raahil Cancel reply