A brief history of “Kanger”

Kanger keeps Kashmiris warm in chilling winters. In Kashmiri literature Kanger is considered as one’s beloved. Moti Lal Saqi writes in praise of Kanger,

“Kashmir and Kanger are each others identification. Present the brazier anywhere and at anytime you identify Kashmir.”

Godfrey Thomas Vigne in his travel memoir, ‘Travels in Kashmir, Ladak, Iskardo, the Countries Adjoining the Mountain-Course of the Indus, and the Himalaya, North of the Panjab, mentions, “The value which a Kashmirian sets upon his Kangri may be known from the following distich:

Ai kangri! ai kangri!

Kurban tu Hour wu Peri!

Chun dur bughul mi girimut

Durd az dil mi buree.

(Oh, kangri! oh, kangri!

You are the gift of Houris and Fairies;

When I take you under my arm

You drive fear from my heart.)

The word ‘Kanger’ according to De Hultzseh seems to be derived from the word ‘Kasthangarika” a compound of Kash (wood) and Angarika (fire-embers). Auriel Stein also agrees that it is derived from the same word . This etymology gains credence from early textual references in Kalhana’s Rajatarangini (12th century) and Mankha’s Sri Kanthcharitam, where the device is also described as hasantika, a portable pot carried in hand that was in regular use during that period.

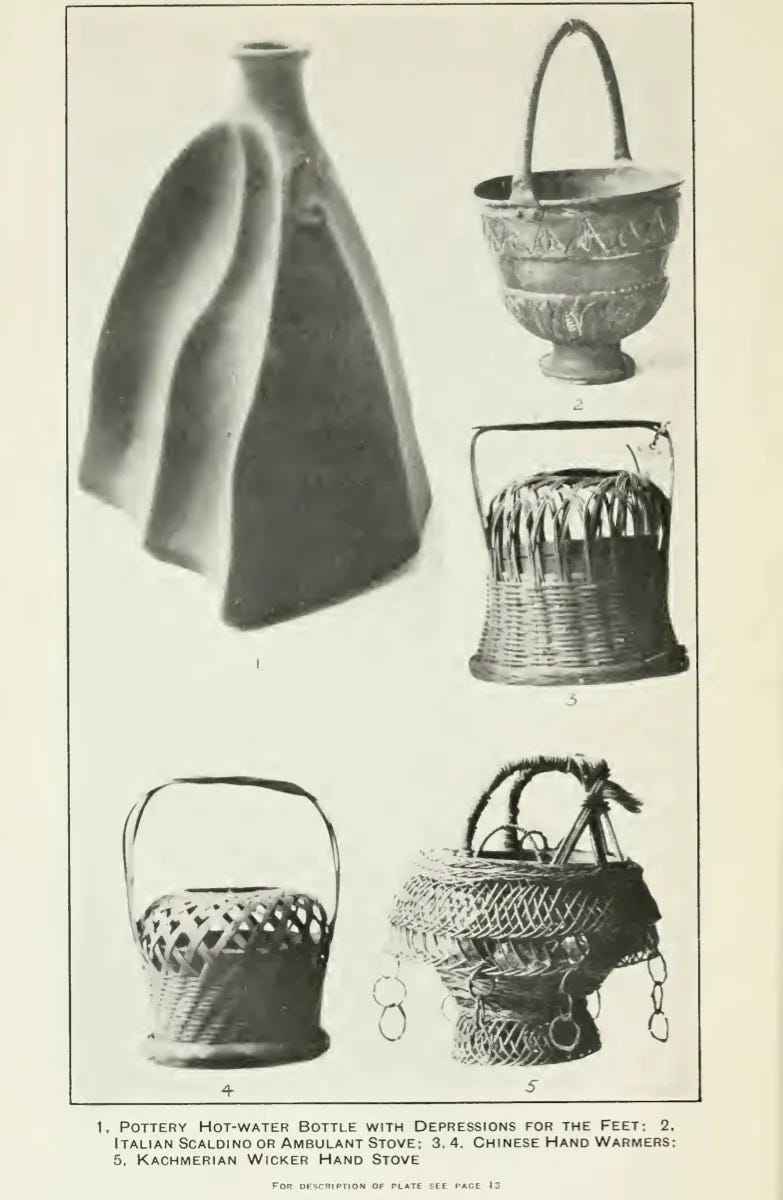

Dr. W.F Elmslie, a well known missionary observed that the Kashmiris probably learnt its use from the Italians who accompanied the retinue of the Mughal emperors. Same view is held by Charles Ellison Bates who in his gazetteer writes: “As a protection against the cold tn winter, the Kashmiris almost invariably carry a kangri or portable brazier. The kangri, which somewhat

resembles the Italian scaldino, consists generally of two parts, an earthenware

vessel (kandal) about six inches in diameter, into which is put a small

quantity of lighted charcoal, and an encasement and handle of wicker

work. Sometimes, however, it is destitute of the wicker work, and theu

it is called manan. As the dress of the Kashmiri is of a loose fashion,

the kangri can be placed in immediate contact with the skin of the

abdomen and thighs, where in many cases cancer is in process of time

generated. It has been surmised that the Kashmiris learned the use of

the kangri from the Italians in the retinue of the Mogul Emperors, who

were in the habit of visiting Kashmir.”

In winters no lower middle-class woman in Florence walks outside without carrying Scaldino, which according to GMD Sufi resembles the ‘Kanger’. However a few historians and authors go back to twelfth century to trace its usage and origins. In ‘The Symbolism of East and West’ (1900), Mrs. Murray Aynsley comments on the work of Eugene Hultzch and observes that he “has shown that the use of portable fireplaces or braziers was known in in Kashmir – as early as the twelfth century C.E., and here we have their use in Persia (and if [Pietro] Della Valle‘s word tennor be right, in Arabia also), as well as in Spain and Italy, in a manner implying a long previous history.”

In a context related to life, Pandit Kalhana mentions Kanger in terms of a general theory,

“Man’s efforts are comparable to the avers in the brazier. Sometimes it burns to annihilate anything even if it seems cold, Sometimes as it may be irony of fate, it inflates ones mouth while puffing”

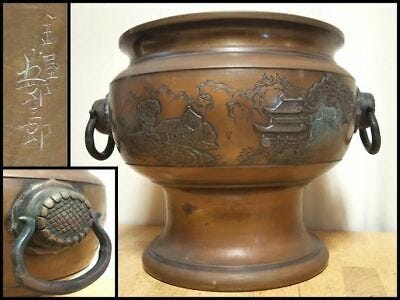

A similar vessel is also used in Japan. Although it is not clear when Japanese braziers were first used, the oldest existing Japanese brazier is believed to be one known as ‘Dairiseki sei Sankyaku tsuki Hoya’(three-legged marble hoya) stored in the Shoso-in treasure repository. The Japanese pocket stove is much advanced. It employs a specially prepared fuel with origins in ancient experiments to produce a slow match for preserving fire for a long time. The pocket stove is made of copper or tin with a perforated slid and is designed to fit the wearer. The cartridges of special charcoal are filled in it and lighted up and the lid is closed and the user enjoys that warmth for half a day with the special Japanese charcoal.

Chinese stove is quiet similar to Kashmiri Kanger in that it consists of a ceramic pot which is encased in small bamboo sticks. The whole structure is balanced upright of a wide base so as to prevent tipping over.

The French have on corresponding to it in their “Chauffer chemic” or pot of charcoal fire.

Similar braziers are available in Iran, Arabia, Spain and Italy as already mentioned above in Mrs. Murray’s quote. Delle-Valle’s word tenor or perhaps ‘Tannur’ in Arabia or in present times in Kashmir the word ‘Tannuri’ is an indication that such Baziers were not uncommon to human civilisation. However the crafting technique is novel in Kashmir.

Kanger has mainly three parts, the inner most earthenware to the ‘Kundal’. The institution of pottery during its growth was owned by the professional potters, called Krals, inhabiting villages assigned for the same occupation. Many of these villages situated the south of the Wular Lake were enclosed by artificial embankments and corresponded in shape to the description of Kundal or ring. Even today two of these villages UtsaKundal and Mar-a-Kundal are situated together near the left bank of the Jhelum. Auriel Stein had been able to locate them at about 74° long and 34° lat. In their descriptions of the Wular Lake, Kalhana and Jonaraja describe a village Suyyakundal, situated on the outskirts of the Lake in their respective Rajtaranghinis.

The outer woven grills of Kani branches made out of witch hazel (Parrotia jacquemontiana), the plant known as ‘pohh’ in Kashmir. Amongst the other branches used are Kani of Posh, Len, Kech and so on. A ring attached to it at its back hangs the chain or ‘Tsalan’, sometimes made of wood sometimes made of metal.

There are various types of Kangers according to decoration, durability and antiquity. These include “Run-dar Kanger”, “Sarposh Kanger”, “Zajeer” and “Zeenadar” Kanger. One of the crude forms of Kanger is called “Manun” mainly used by the boatmen. Among famous Kangers are included: ‘Bandapur Kanger”, “Islambaed Kanger” and “Tsar Kanger”. ‘Isband Soz” is actually a brazier to emanate scent to the assembly of invitees or “salars” on happy occasions.

The travellers throughout the world as well as the officials who used to visit Kashmir have talked about the harmful effects of Kanger. Moorcroft and Trebeck in their travel memoir, “Travels in Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan, and the Punjab in Ladakh and Kashmir in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara” mention “Kashmirians usually carry under theirtunif an earthen pot with a small quantity of live charcoal, a practice that invariably discolours and scars the skin”.

Lawrence in his ‘Valley of Kashmir”, talks about how “small children use Kanger- day and night and a few of the people have escaped without burnt marks caused by the carelessness at night’.

In its historical development, Kanger has assumed a political significance and a emotional iconography as well. In ancient Kashmir when courtiers used to deliberate over the succession issue of the kings, Kanger was hurled at the opponents. On the very first day of Hartal following the theft of sacred relic from Hazratbal Shrine, People collectively assaulted a leader with their Kangers in the Amirakadal Chowk. During early nineties, those carrying Kangers in their Pherans (cloaks) were often subjected to frisking and searches, possibly because the pout inside the pheran giving an impression of a weapon being carried. In the disagreements between people, Kanger has universally been accepted as the most convenient instrument of harming the opponent.

Kanger remains beloved to the Kashmiri, historian Hassan Kuihami writes:

“What Laila was to Majnun’s bosom, so is the Kanger to a Kashmiri”

Leave a reply to Karan Mujoo Cancel reply