سب کہاں کچھ لالہ و گل میں نمایاں ہو گئیں

خاک میں کیا صورتیں ہوں گی کہ پنہاں ہو گئیں

Not everything became visible as tulips and roses

In the soil- what countless faces must be hidden

History narrates its story through many languages: some etched in the beauty of scripture and stone, others whispered through the colours of art, and numerous others silent in the grace of ruins.

Contrary to the popular belief that ancient Kashmir lay at the peripheries of civilisation, a marginal outpost in the story of ancient world, the history testifies otherwise. Kashmir stood at the crossroads of many cultures, many civilisations and many stories: an epicentre of exchange, emotion, and identity. Among the many archaeological witnesses to this historical centrality is the ancient Buddhist monastery located at Harwan. Its remarkable terracotta tiles testifying Kashmir’s cosmopolitan past.

Located approximately 12 kilometres northeast of Srinagar near the Mughal Shalimar Gardens, the monastery represents one of the earliest and most significant archaeological sites of Kashmir. It was first noticed in modern times, around 1895, when part of its decorated brick pavement was unearthed by accident during the construction of the Srinagar waterworks. These fragments continued to be discovered about the hillside, and R. C. Kak illustrated several in his 1923 catalogue of the Sri Pratap Singh Museum. During the same decade, Kak conducted an excavation, briefly noting his discoveries in the Illustrated London News and later publishing them in detail in his book on Kashmir monuments.

The Buddhist monastery was founded during the Kushan period (2nd century CE) and later expanded during the Hephthalite (Hun) period (mid-5th century CE).

(Courtesy: Manan Shah/World History Encyclopedia)

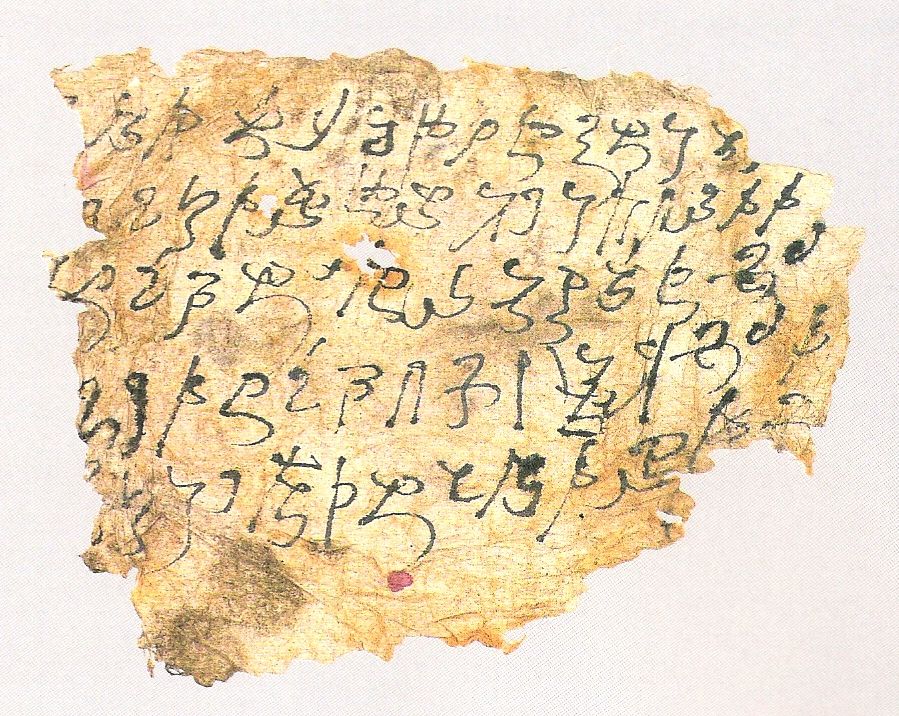

The tiles found in the complex, which bear numerals inscribed in the Kharosthi script, provide substantial evidence of the date of the monument as well. Kharosthi script had been in vogue in north-western India between the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE. R. C. Kak accordingly places the date of the tiles at 300 CE, and consequently that of the diaper-pebble masonry as well.

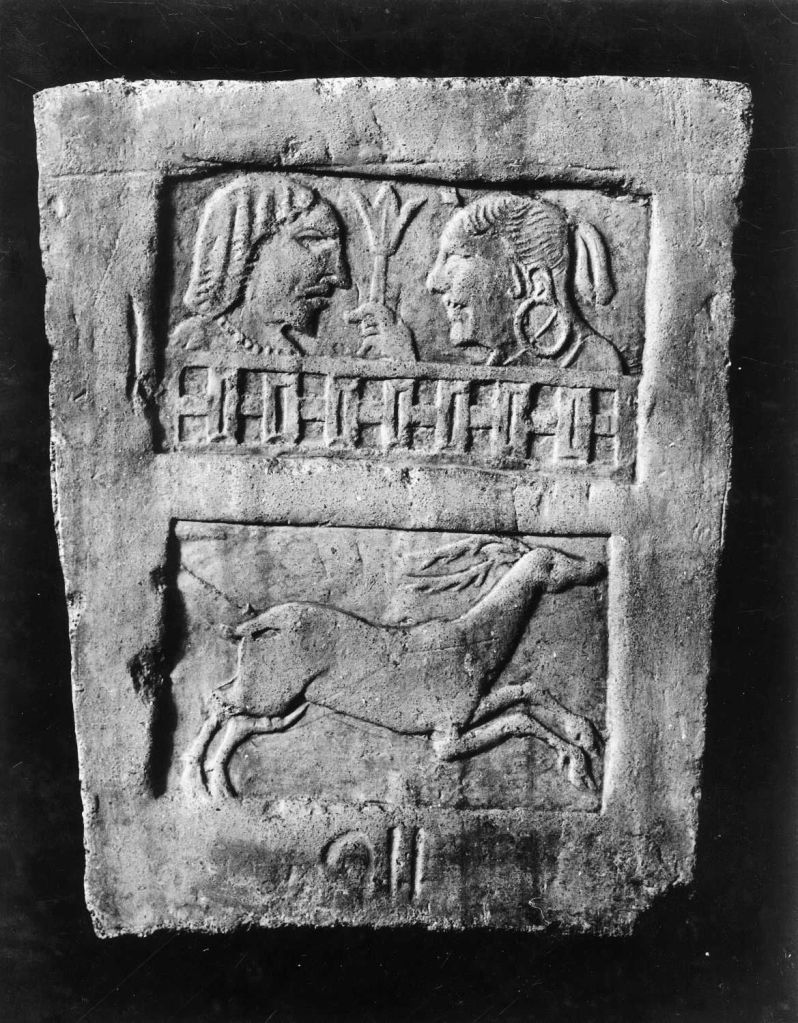

Drawing further upon the facial characteristics of the human figures in the clay motifs of the structure, noted scholar Iqbal Ahmad comments, “These bear close resemblance to those of inhabitants of the regions round about Yarkand and Kashgar, whose heavy features, prominent cheekbones, narrow, sunk, and slanting eyes, and receding foreheads are faithfully represented on the tiles. Some of the figures are dressed in trousers and Turkoman caps. The only period when Kashmir had any intimate connection with Central Asia was during the supremacy of the Indo-Scythians and Kushans in the early centuries of the Christian era, when Kashmir formed part of the Kushan Empire, which extended from Mathura in India to Yarkand in Central Asia.”

According to Kak, who also supervised temple excavations in 1925, the monastery is a “wonderful pavement of the courtyard round the temple, consisting of large moulded brick tiles having various shapes and forming different patterns. The favourite pattern seems to have been a large disc consisting of several concentric circles with a single central piece. Each circle is composed of a series of arc-shaped tiles of different dimensions; one of the tiles measures 40 cm in length, 34 cm in width and 4 cm in depth, each shaped with a special motif.”

The uppermost terrace contains an apsidal temple built in the distinctive diaper-pebble masonry style. It features a spacious rectangular antechamber with a circular sanctum at the rear. This temple is surrounded by a courtyard magnificently paved with decorated terracotta tiles which are arranged in concentric circular patterns. The middle terrace reveals highly damaged rubble-built walls and additional diaper-pebble structures, while the lower terrace exposes a triple-based stupa of medium size and sets of rooms that may have served as chapels or residential quarters.

The tiles depict a unique grammar of cosmopolitan art. They exhibit remarkable artistic sophistication and iconographic diversity. Every clay motif is a microcosm of the ancient world’s inter-connectedness.Wvery remaining fragment showcases a unique blend of religious symbolism, everyday imagery and artistic specimens borrowed from numerous cultures.

(Courtesy: Manan Shah/World History Encyclopedia)

In his monumental paper, Enigma of Harwan, Robert Fisher notes:

“Such a dynamic and possibly colourful floor treatment, not common by any means, is known from much earlier times and over a wide geographic area. Textiles no doubt have a long history of use as colourful and decorative floor covering. Assyrian palaces from the late eighth century BC made this longer lasting by carving such decorative textile designs into stone slabs but limited only to thresholds. They also utilised baked bricks set into bitumen as floor covering. In the ancient Mediterranean world, it was common to overlay beaten earth with another material, such as brick or gypsum, then a layer of plaster. In Egypt and Crete, this was sometimes painted. Hellenistic Greece was known for pebble floor mosaics as early as 300 BC, and at Pella, inlaid terracotta strips were utilised to help define portions of the pictorial subject. In addition to their fame as producers of colourful mosaic floors, the Romans also utilised terracotta squares. Apparently, glazed decorative floor tiles did not appear in the West until the thirteenth century as a result of Islamic influence. However, none of these cultures utilised decorative clay or terracotta tiles to the extent found at Harwan, although Parthian and Sassanian cultures, occupying most of Iran and West Asia from the third century BC until the coming of Islam in the seventh century, did continue that region’s tradition of clay as a primary construction material.”

(Courtesy: Manan Shah/World History Encyclopedia)

In his book Indian Architecture: Buddhist and Hindu Periods, Percy Brown writes about the unique characteristics of motifs:

“Pressed out of moulds so that the same pattern is frequently repeated, although spirited and naïve in some instances, they are not highly finished productions, but their value lies in the fact that they represent motifs suggestive of more than half a dozen alien civilisations of the ancient world, besides others which are indigenous and local. Such are the Bharhut railing, the Greek swan, the Sassanian foliated bird, the Persian vase, the Roman rosette, the Chinese fret, the Indian elephant, the Assyrian lion, with figures of dancers, musicians, cavaliers and ascetics, and racial types from many sources, as may be seen by their costumes and accessories.”

The terracotta tiles display an astonishing array of decorative elements that point to multiple civilisational influences. The reference to Bharhut railing connects them to the famous 2nd century BCE Buddhist stupa in Madhya Pradesh, known for its distinctive railing designs with lotus ornaments and medallions. This represents the indigenous Indian Buddhist artistic tradition.

The terracotta figurines reflect a discernible Hellenistic influence. The enduring imprint of Hellenistic aesthetics and intellectual ideals can be traced to the Gandhara region of which Kashmir constituted both a geographical and political extension. The Gandhara School of Art, which flourished between the first and fifth centuries CE and persisted in parts of Kashmir and Afghanistan until the seventh century CE. It provided the principal conduit for the diffusion of artistic and cultural elements. The Greek influence manifests in the Greek swag or festoon motif, carved ornamental arrangements of flowers, fruit, and foliage tied with ribbons that sag in the middle. This decorative element was freely used by ancient Greeks and Romans and represents Hellenistic artistic influence that had reached Kashmir.

The Persian motif, Sassanian foliated bird, depicts nimbate birds embellished with imagery of Sassanian royal iconography i.e. garlands with drop pendants and beaded halos. The Sassanian Empire (224–651 CE) had significant cultural exchange with the regions around Kashmir, and its distinctive foliated bird designs and metalwork influenced local artistic traditions.

Persian vases in ancient art symbolised abundance and fertility, and are often depicted overflowing with flowers or vegetation. The Roman rosette: a round, stylised flower design was extensively used in Roman sculptural objects and became an important decorative motif. Originally derived from Mesopotamian art (associated with the goddess Ishtar), it spread throughout the Roman Empire and reached Kashmir through various cultural exchanges.

(Courtesy: Los Angeles County Museum of art)

Known in China as the “cloud and thunder pattern” (leiwen or huiwen), Chinese fret (meander) is a decorative pattern of angular lines symbolising life-giving rain. The meander motif occurs in Chinese art from Neolithic times and was found on bronze vessels of the Shang and Zhou dynasties.

The Indian elephant appears frequently in the tiles as a distinctly Indian motif, representing one of the neighbouring elements in the artistic vocabulary. The lion in Mesopotamian and Assyrian art symbolised royal authority and the forces of chaos that the kings defeated. Lions appeared in Assyrian works from the Early Dynastic Period through the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

(Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of art)

Apart from these the tiles also depict conventional flowers and lotus plant leaves, waterfowl (ducks, geese, cocks) with flower petals in their bills, fighting animals (rams, cocks), elephants, deer, and cows with their young, archers on horseback in Parthian dress, couples conversing on balconies, musicians playing drums, flutes, and cymbals, dancing figures, emaciated ascetics, and soldiers in armour.

(Courtesy: Metroplitan Museum of art)

The terracotta tiles themselves are very important pieces of evidence about Kashmir’s place in the Kushan Empire and its artistic growth. In these tiles, Kashmiri artists used terracotta as their main medium, which set them apart from artists in other Kushan territories, where stone was more common eg. Mathura where red sandstone was used. This preference for terracotta implies that Kashmir had established an indigenous artistic tradition utilising clay prior to the Kushan conquest. The Hellenistic influences introduced by Gandharan artists were integrated into this pre-existing local tradition rather than replacing them entirely.

Similar terracotta tiles that also display artistic characteristics of the Kushan period have been discovered at locations such as Huthmura, Semthan, and Darad Kut. These tiles’ Hellenistic influence places them in line with larger Gandharan artistic traditions of Harwan.

What makes Harwan truly exceptional is not merely the presence of these diverse motifs but their harmonious integration on a single site. Kashmir’s status as a cross-section of civilisations is reflected in this extraordinary cultural convergence.

Kashmir was incorporated into a vast trading network during the Kushan period that ran through the Indian subcontinent, China via the Silk Road, Persia and Central Asia (the Sassanian and, and the Greco-Roman Mediterranean world.

Kashmir is one of the most compelling examples of globalisation in the ancient world and the Harwan terracotta plaques stand as testimony to Kashmir’s unique position in ancient world history: a place where East met West, where Indian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Chinese, and Central Asian artistic traditions converged and created something entirely new. They also shatter all the narratives that twist the history of valley for vested political interests and try to deconstruct its past into a cultural monolith, representing only one or a few people. These tiles exemplify how Kashmir was neither an inwardly looking cultural sphere nor a silent recipient of outside influences. Like a civilisational synapse; it absorbed and re-expressed influences in its own idiom.

Leave a comment