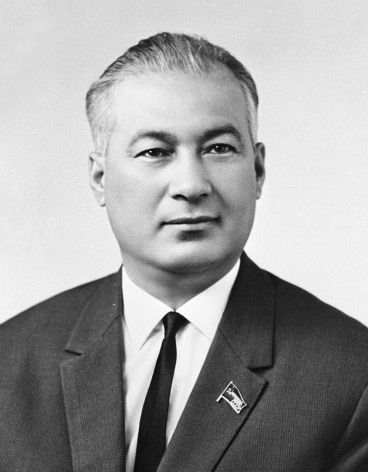

Rashidov Sharof was a prominent Uzbek politician, diplomat, and public intellectual.

He was the first secretary of the Communist Party of Soviet Uzbekistan from 1959 to 1983, and a de facto leader of the Samarkand faction of Uzbek politics. During Rashidov’s tenure, great developments were made in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in the fields of agriculture and industry. The Tashkent Aviation Production Association became one of the largest aircraft producers in the world, and in 1969, the Muruntau mine began extracting gold, which became one of the most important mines in the USSR.

He was actively involved in numerous diplomatic missions all over the world, including the organization of peace talks in Tashkent, when India and Pakistan signed the Tashkent Declaration peace agreement in 1966.

Sharof Rashidov was twice awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labour and received the prestigious Lenin Prize. He was honored with ten Orders of Lenin, along with numerous other high Soviet decorations, including the Order of the October Revolution, Red Banner of Labour, and two Orders of the Red Star. These awards reflected his prominent role in Soviet politics, culture, and wartime service.

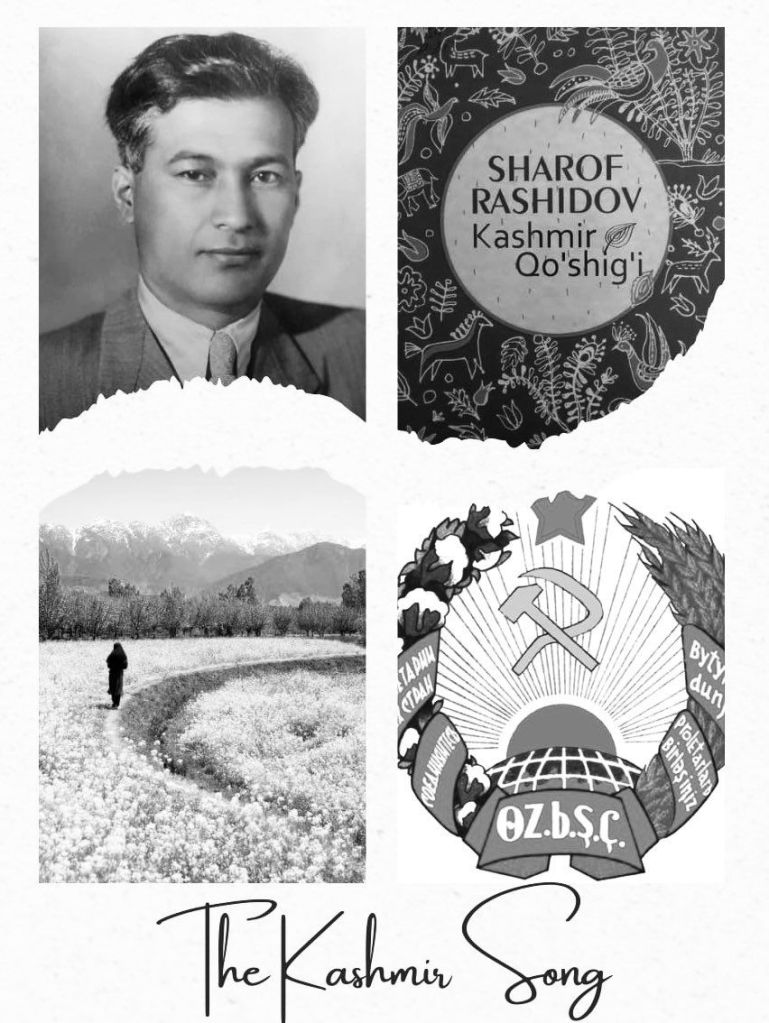

One of the greatest literary and probably the most translated works of Rashidov is “Kashmir qoʻshigʻi” or The Kashmir Song.

Originally written in Uzbek and inspired by an opera “Bombur te Yamberzel” (The narcissus and the bumblebee) by Dina Nath Nadeem that was played during the official visit of military leader and Marshal of the Soviet Union Nikolai Bulganin and First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party’s Central Committee Nikita Khrushchev to Kashmir, the novella is a dramatic retelling of this traditional Kashmiri legend: the love of Bambur (the bee-king) and Nargis (the spring narcissus), symbolizing the triumph of life and love over the harsh forces of nature blizzard (waav) and Harud (autumn). It weaves themes of nature’s cyclical renewal with struggles, such as cultural resilience and resistance to colonial forces.

It was first published in Uzbek (1956), then translated into Russian (1958) and translated in English in 1979. The were numerous Farsi and Urdu translations of this legend as well. The Persian translation was done by the celebrated Tajik poet Mirzo Tursunzoda.

The story’s popularity sparked several artistic adaptations, including a ballet by Georgy Muschel in the early 1960s and a Soviet-era cartoon in 1965. In 1984, Rashidov’s novella inspired a Soviet film, “The Legend of Love.”

Some beautiful lines from the poem:

Agar birlashsak, do ‘stlar,

(If we unite, friends,)

Har ganday yov gochadi.

(Any enemy will flee.)

Axir, kichik yulduzlar,

(After all, little stars,)

Birlashib nur sochadi

(Will shine together)

Agar birlashsak do ‘stlar,

(If we unite, friends!)

Har ganday yov gochadi.

(Any enemy will flee.)

“If we unite, friends, any enemy will flee,” an unmistakable communist call to collective action and proletarian solidarity. It invokes the Marxist idea that the power of the people, when organized and conscious, can overcome any form of oppression.

The second couplet, “After all, little stars / Will shine together,” transforms cosmic imagery into a metaphor for the unity of the working class. This reflects a dialectical idea: the transformation of the individual into a powerful collective force, echoing Lenin’s insistence that organization turns weakness into strength.

Some more lines that depict resilience and resistance against hardships:

Agar Bo’ron tursa, to ‘ssa yo ‘lingni,

(- If the Stormstops, blocks your way,)

Xorudlar yopishsa, uzsa go ‘lingni,

(If the Choruds attack, cut off your hand,)

Qumlar olov bo ‘lib kuydirsa agar,

(If the sands burn like fire)

Yo ‘llaringni to ‘ssa azim daryolar,

(Great rivers block your way,)

O’ylagan o ‘yingdan gaytarmi diling,

(Will you change your mind,)

So ‘yla, afsusini aytarmi tiling?

(Tell, will you regret then?)

– Do ‘stlar, to ‘solmaydi Bo’ron yo ‘limni,

(“Friends, the Storm will not stop me,”)

Uzib tashlolmaydi Xorud qo ‘limni.

(Chorud cannot break my hand.)

Qumlar olov bo lib kuydirganda ham, (Even when the sands burn like fire,)

Daryolar toshsa ham, men turib bardam,

(Even if the rivers overflow, I will stand,)

O ‘ylagan o ‘yidan gaytmaydi dilim,

(I will not change my mind,)

Afsus qo ‘shig ‘ini aytmaydi tilim”.

(My heart will not sing the song of regret)

At its heart, the verses dramatizes the revolutionary subject standing firm amid natural and social catastrophes. The storm, sand-fire, and raging rivers are metaphors for the many obstacles placed before the people by oppressive systems “The storm will not stop me… Chorud cannot break my hand” transforms into a hymn of proletarian courage.

Dina Nath Nadim wrote “Bombur ta Yambarzal” in 1952 after himself being inspired by the Chinese opera “The White Haired Girl” during his visit to Beijing. Nadim’s opera was first staged at Nedou’s Hotel, Srinagar in 195e, and became hugely popular with Kashmiris who couldn’t stop singing its songs. The most famous song from this opera was “Bumbro Bumbro Shaam Rang Bumbro“. The opera served as an allegory about American Capitalism versus Soviet Socialism, with the forces of good (Bombur, Yambarzal, and other flowers) representing peace and prosperity, while the antagonistic forces of Waav (blizzard) and Harud (autumn) symbolized imperialistic agencies dividing people.

This was created within the context of the 1953 Kashmir Conspiracy Case when Sheikh Abdullah was arrested, and progressive writers like Nadim promoted cultural programs reflecting anti-imperialist unity. Dina Nath Nadim received the Soviet Land Nehru Award in 1971 from the USSR government. Remarkably, when proposed for this award, the selection committee discovered that despite being the preeminent poet of Kashmiri language, Nadim had not published a single book. The citation ultimately honored him for “the totality of his works”. He later received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1967 specifically for “Bombur te Yambarzal”.

The re-interpretation of a traditional Kashmiri legend through a communist lens illuminated universal themes of resilience, hope, and survival, marking it as one of the most remarkable contributions to twentieth-century literature.

Leave a comment