What an extraordinary way the reed pen has of drinking darkness and pouring out light!

Abu Hafs Ibn Burd Al-Asghar (Andalusian poet)

Calligraphy is one of the most stark and straightforward forms of artistic tenor, hence an anonymous thinker describes it as

“More powerful than all poetry, more pervasive than all science, more profound than all philosophy are the letters of the alphabet, twenty-six pillars of strength upon which our culture rests.“

French Calligrapher Claude Mediaville in her monunental work, “From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting”, describes it as “the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner”.

We do not know when exactly Kashmiris began writing but the practice was possibly encouraged by the needs of the Buddhists traders and missionaries. Although the Chinese pilgrim Faxan (about 400 c.e) is silent about copying books, his more illustrious follower Xuanzang (seventh century) had a number of scribes at his disposal. The type of Kashmiri script his scribes used would have been similar to that seen in the inscription on the base of the Priyaruchi’s brass Buddha. A few years later the Tibetan mission arrived to adopt this script for their own language. However, no early manuscripts have survived from Kashmir or elsewhere with this early Kashmini script or with the later Sharada script. Examples of Sharada script of the ancient period can be found in epigraphs and inscriptions on metal images and of the Sultanate period even on Islamic tombs. While these inscriptions are sometimes visually attractive, they do not constitute conscious efforts in the art of caligraphy that one encounters in east Asian cultures.

According to C. Stanly Clarke, calligraphy as an art of decorative writing was highly esteemed in the East and contributed greatly not only in diffusing but in preserving its languagues. This extraordinary appreciation of a minor art was undoubtedly engendered by the Muhammadan law, which prohibited the representation of living things in art, the artistic spirit craved for satisfaction and found it in calligraphy.

The art of rendering emotions into beautifully curved lines was enkindled further by the terse spritual needs of a culture which came into contact with the Islamic tradition of embellisihing names and speech of God as a means to attain the intangible Supreme. An artistic extention to melodiously reciting Quran.

Therefore the origin of calligraphy in Kashmir finds its way with the arrival of Bulbul Shah and subsequent conversion of Renchan Shah to Sultan Sadr-ud-Din. Bulbul Shah is said to have been the first calligrapher in Kashmir.

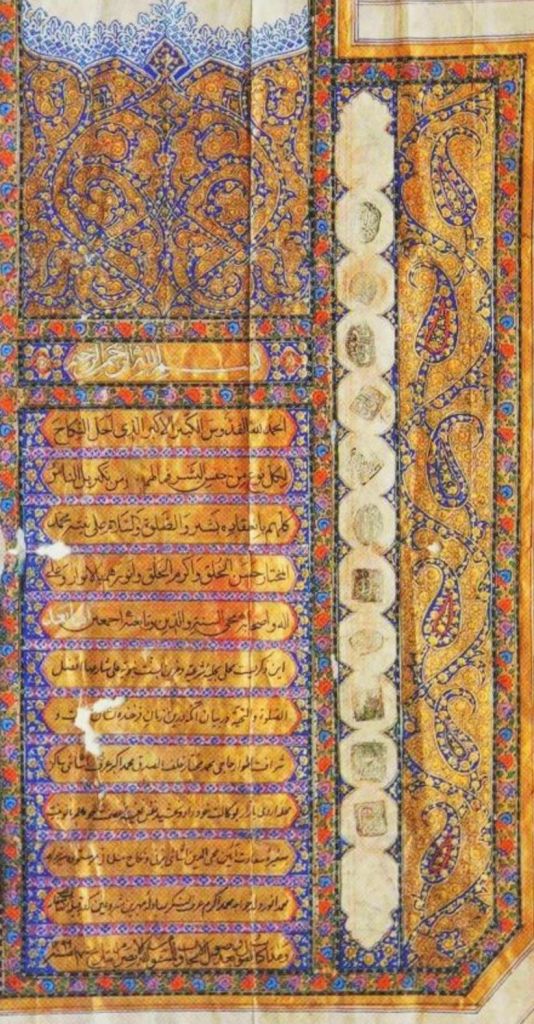

The high culture of Kashmir, owing to its strong Islamic undertones, preferred calligraphy to painting and sculpture. Shahi Khan, polpularly called Zain-ul-Abideen was the first king to invite caligraphers all the way from Iran and introduced the use of paper instead of bhojapatra (Himalayan Birch tree which was used for writing in ancient times). He ordered writing of numerous copies of Kashaf, a well known commentary of Quran by Allama Zamakhshari.

However, Kashmiri penmanship reached its zenith under the Mughal rulers. Kashmiri artists are known to have invented an indelible ink during this period and recieved handsome rewards for it. The scripts adopted in Kashmir, as recorded by Diwan Kirpa Ram in his Gulzari Kashmir were either in Arabic or in Persian. The styles were Kufi, Naskh, Makramat Suls, Riqa and Raihan in Arabic and Nastaliq Shikast, Gular, Nakhan Shikast, Aniz and Shaifa in Persian.

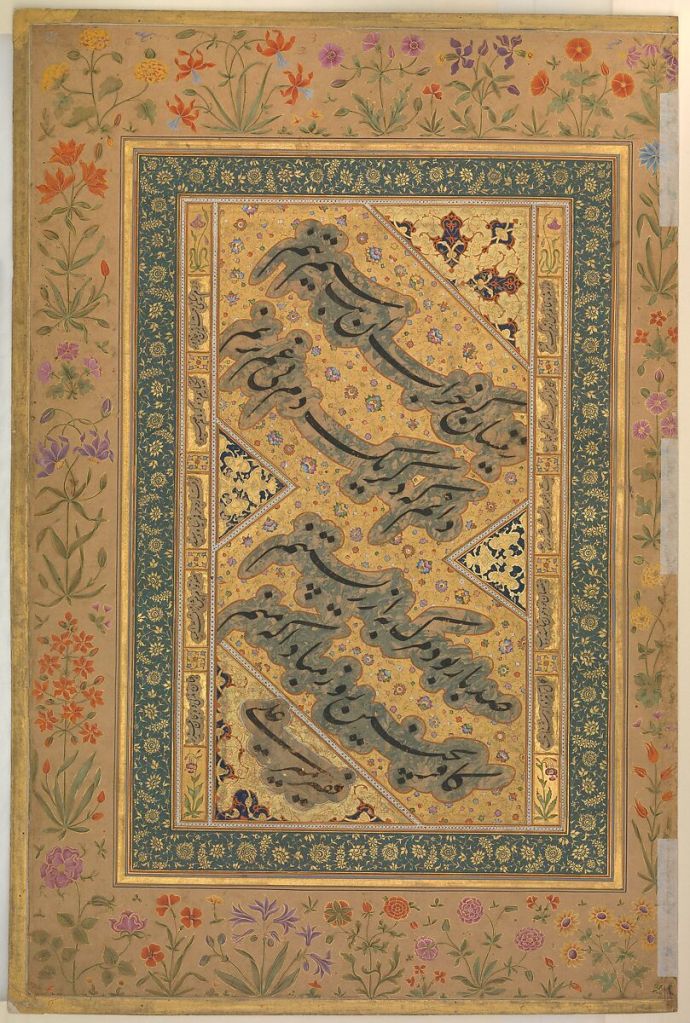

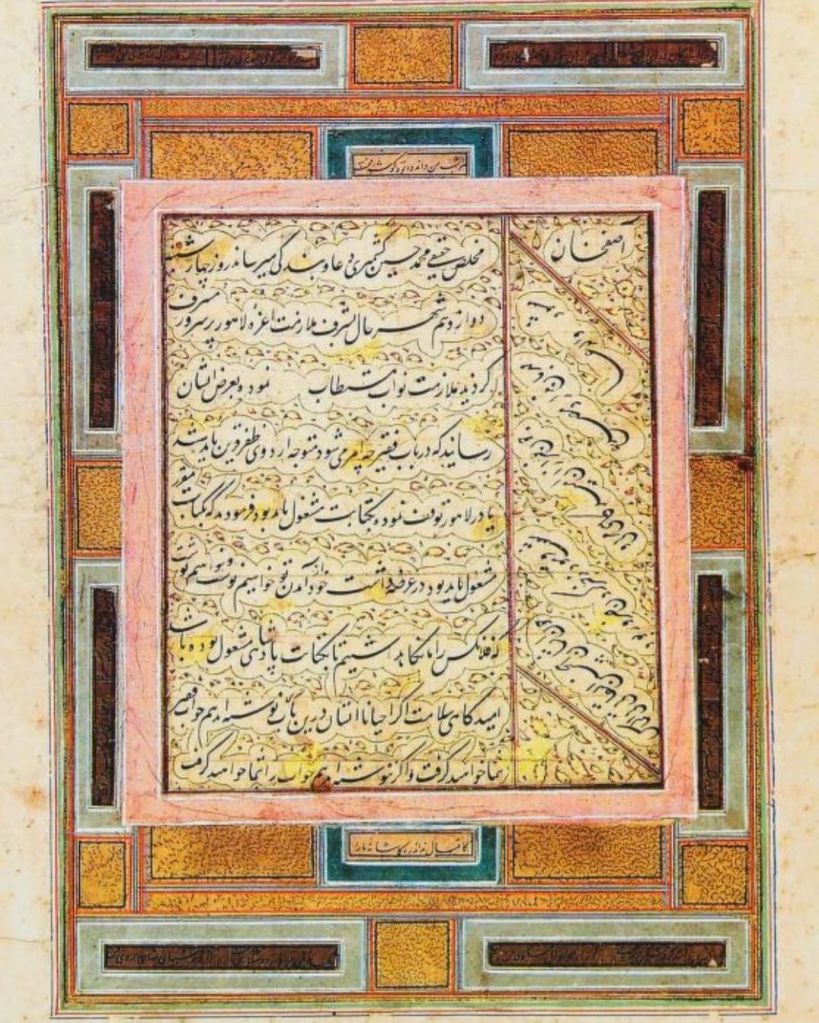

Abul Fazl praises a Kashmiri calligrapher Muhammad Hussain of Kashmir as Jadu Raqam (writer of magic). His Kashmiri mentor was Moulana Abdul Aziz and both may initially have worked for Mirza Haider Dughalt who brougth them to the attention of the imperial court. Muhammad Hussain became the court calligrapher of Akbar and was honored with the title of Zarin Qalm (the Golden Pen). Abul Fazl praises Hussain as a master calligrapher, having surpassed all his teachers, with his muddat (extentions) and dawair (curvatures) showing proper proportion amd ratios to each other.

In the Ain-i Akbari Abu’l Fazl describes him thus:

“The artist who, in the shadow of the throne of His Majesty, has become a master of calligraphy is Muhammad Husain of Kashmir. He has been honoured with the title Zarrinqalam, the gold pen. He surpassed his master maulana Abdul-Aziz.., art critics consider him equal to Mulla Mir Ali” (Ain-i Akbari, vol.1, pp.102-3).

Six years after the death of Akbar, Jahangir rewarded Muhammad Hussain Kashmiri with an elephant, as a mark of appreciation to his art. During the reign of Akbar, when Muhammad Hussain enjoyed the highest position as a calligrapher, numerous other calligraphers in the court like Ali Chaman Kashmiri owed their origins to Kashmir as well.

During Shah Jahan’s rule Muhammad Murad Kashmiri was endowed with the title of Shirin Qalm (The sweet pen). He was considered an equal of the great names of the art like celebrated calligraphers Mulla Mir Ali and Sultan Ali.

Other Kashmiri calligraphers attatched to the court of Shah Jahan were Mulla Mohsin, younger brother of Murad, Mulla Baqir Kashmiri etc. They are consideded masters of Nastaliq, Taliq, Nasakh and Shikast in Arabic and Nastaliq, Shikast, Gulzar, Nakhun, Shikast amiz, Shafee and Amiz in Persian.

Names of a few other Kashmir caligraphers are known but almost certainly some of the most competent must have worked for the Mughal royalty and their governors as well as Kashmin patrons, One was Abdal

al-Rahram, the son of Ali al-Kashmiri who, while visiting Mecca, copied a manuscript of holy sites in Mecca and Medina in Arabia.

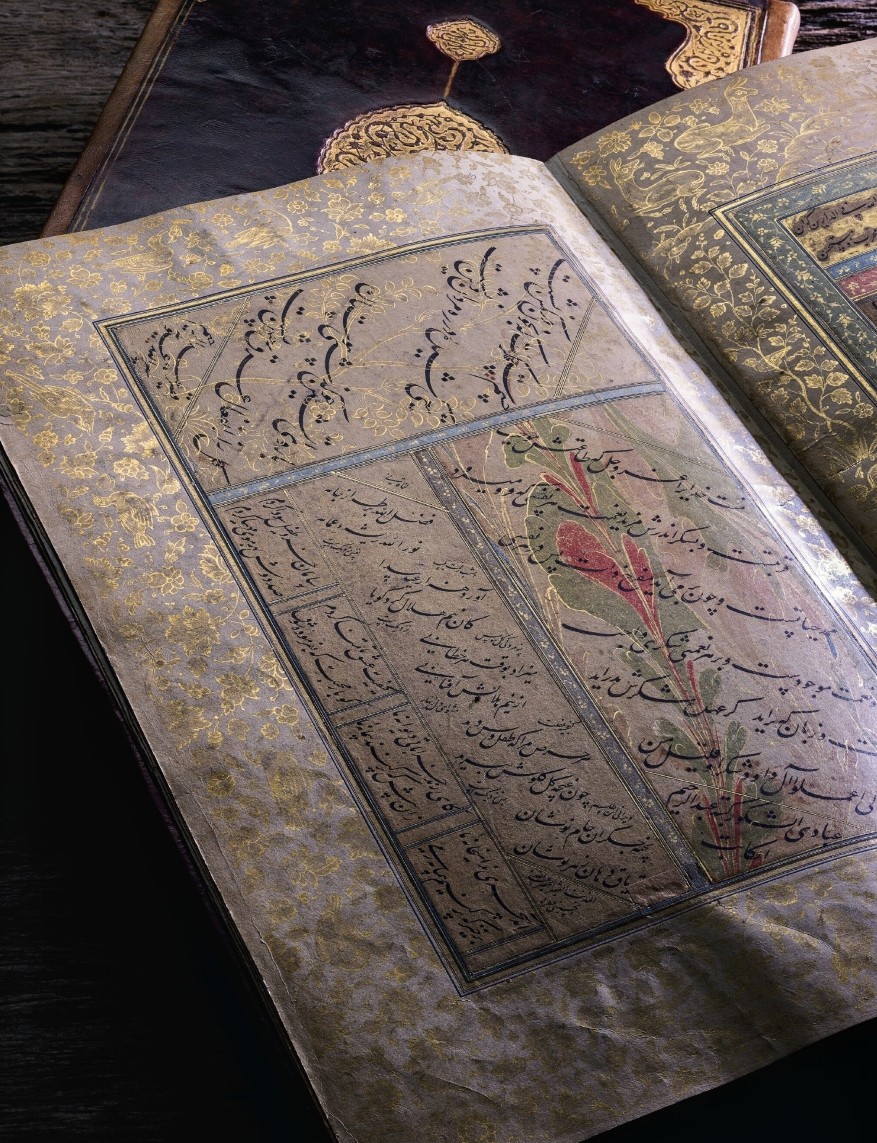

Later Akhund Baha-ud Din and Haider Kashmiri were other famous penmen of Nastaliq style, followed by Yaqub Muhammad son of Murad Kashmiri who excelled in Kufi style and compiled a book on calligraphy. During the rule of Sikh dynasty Murad Baig, Mirza Saif-ud Din, Khwaja Abd-ur Rahman Naqshbandi, Bashir Wani, Mir Habibullah Kamili, Mir Muhiyy-ud Din Akmal and Abd-us Samad Dongi earned a great fame. Muhammad Taqi, Imam Dairwi and Ahmad Ali Kashmiri were famous calligrapher of Raja’s court.

Kashmin calligraphers were greatly sought after in other parts of the subcontinent. Lahore was the closest center of patronage for art and literature, but Kashmiri caligraphers sold their work as far away as Calcutta. This was true of both Hindus and Muslims. The pandits were as proficient in Arabic calligraphy as their Muslim counterparts. Numerous manuscripts of Islamic subjects were copied in Lahore between 1869 and 1873 by Pandit Daya Ram Kaul popularly known as Tota (parrot).

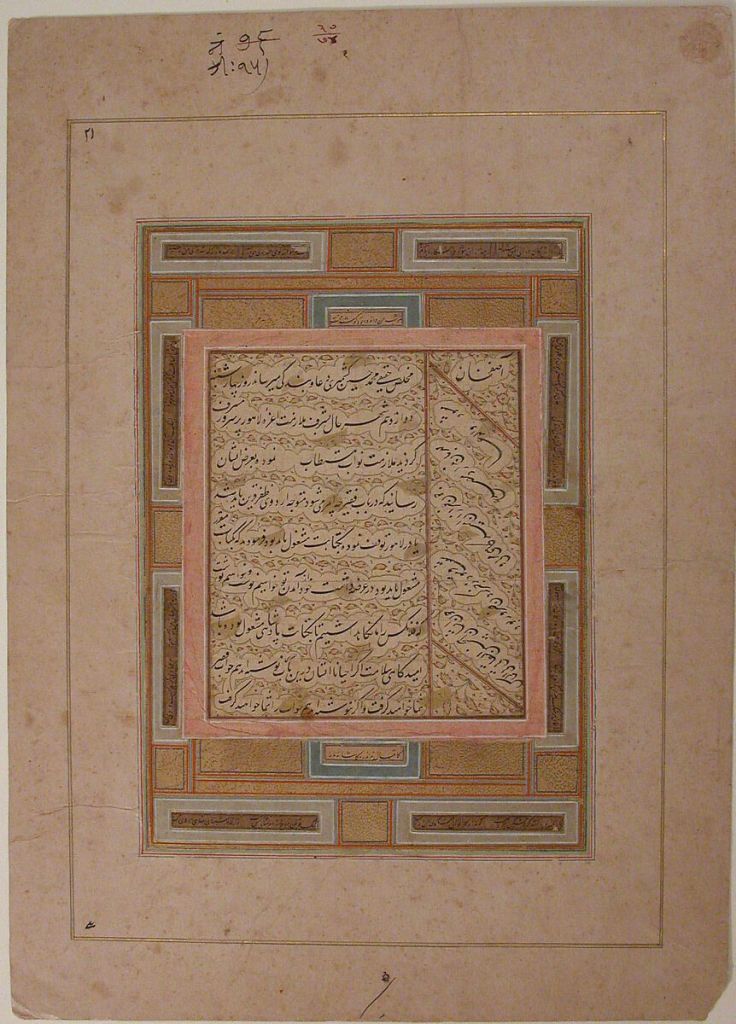

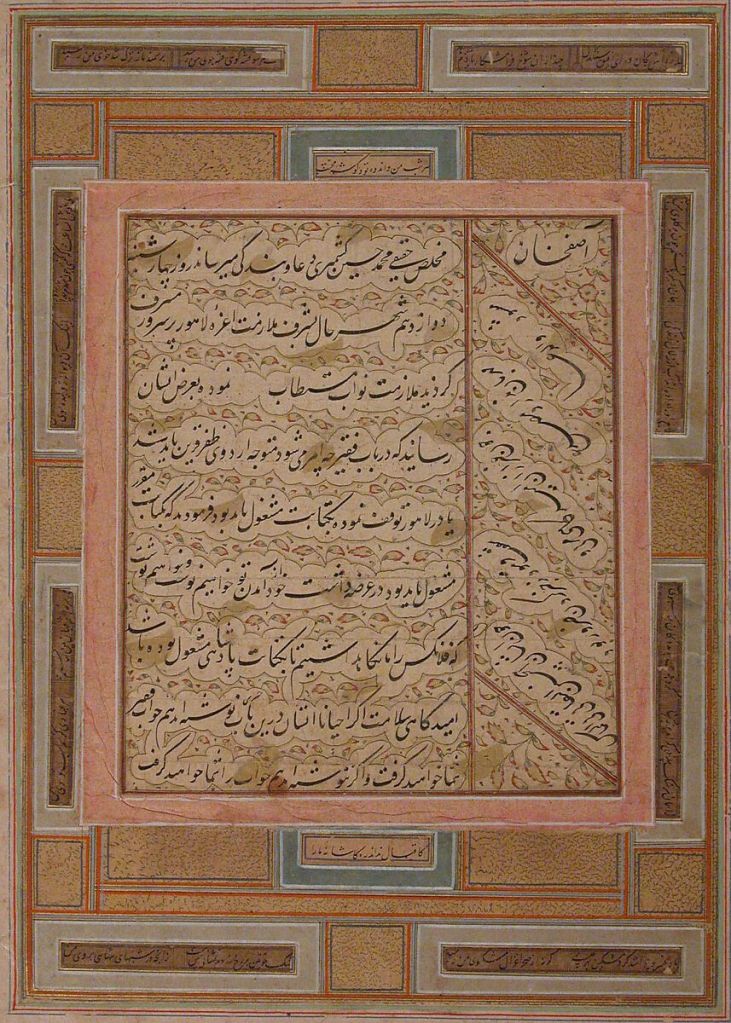

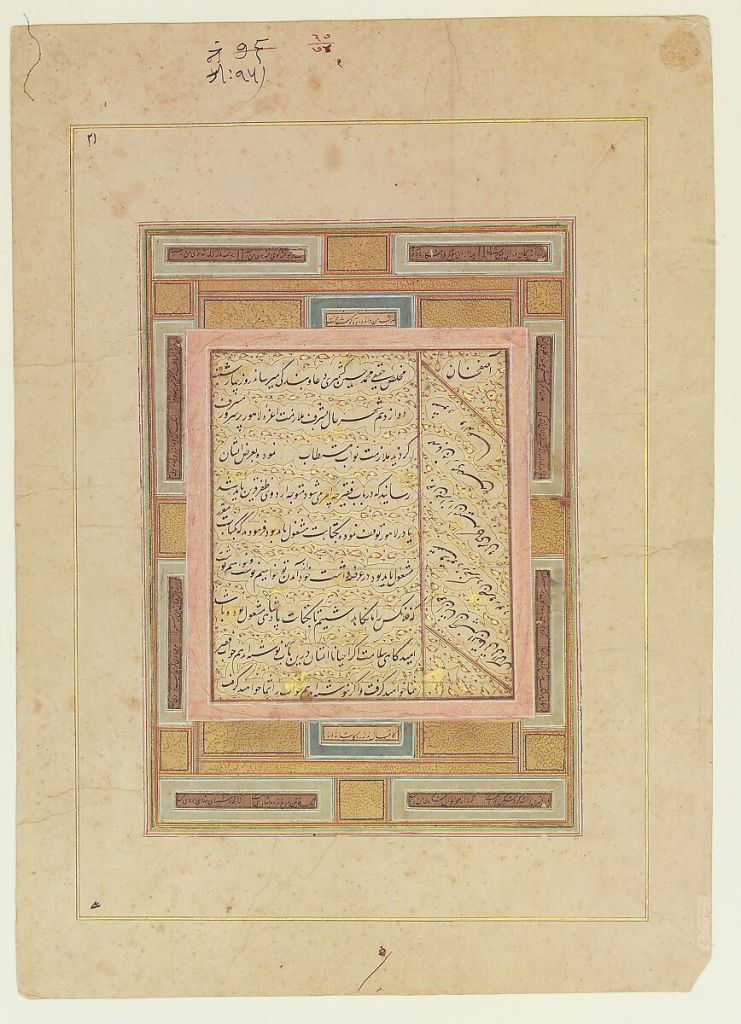

The story of Kashmiri calligraphers can be brought to a conclusiom by mentioning a colophon in a manuscript of Dīvān (collected poems) of Nawab Yusuf Alikhan the nawab of Rampur (in Uttar Pradesh) from 1855 to 1875. The manuscript was copied in Lahore by Muhammad Nazir ‘Ali ibn Sayyid ‘Ilwad ‘Ali Gardizi, and illuminated by Muhammad Hasan ibn Mulla Muhammad Ali, also called khūshnavīs Kashmiri. Khūshnavīs denotes a caligrapher. He is characterized as a great expert on lapidary work, coloring, and gold work, and regarded as a peer of Manil (a legendary instructor of painting in Persia) and equal of the greatest Persian painter, Bihzad.

Leave a comment