Khawar Khan Achakzai

The is no single city in the subcontinent which has produced as many Persian clerisy as has the city of Srinagar. However, while arts and crafts of Kashmir have acquired fame throughout the world, the genius that Kashmiris contributed to the world of literature, especially Persian literature, have remained confined to the forgotten palimpsests.

Early history

Persian language is often said to have entered Kashmir as early as 1000 C.E however the historical accounts consolidate the general adoption of the language during the reign of Shahmiris, until then Sanskrit had been in vogue.

The phases:

According to Girdhari Lal Tikku (Book: Persian Poetry in Kashmir) the timeline of Persian in Kashmir is divided into four phases,

- Early phase under the Shahmiri sultans (1349-1561)

- Court and Sufi poetry under the Shiite Chak rulers (1561- 89)

- Mughal Indo-Persian style (1586-1752)

- Finally a Kashmiri style, developed under the Afghans and the Sikhs.

During the first and second phase, critics have acknowledged around 17 distinguished poets although the number could have been greater. This is the time when Persian was newly wedded to the local literary doctrines and hence a heavy influence of Iranian poetry is quite easily palpable in the Kashmir Persian poetry of this phase. During the third phase around 197 distinguished poets are recognised. The poetry during Mughal era finds tremendous Indo-Kashmiri mixing with Persian, largely due to the presence of people from Agra, Delhi, Kabul etc. in the Kashmir administrative and literary circles. In the fourth phase there is profound expression of the local Kashmiri idioms and metaphors in a unique kind of indigenously produced Persian compositions.

A few notables:

The pre-Mughal Era begins with Sultan Sikandar and the arrival of Sufi Saint Syed Ali Shah Hamdani. However, even before his arrival, due to ongoing trade between Central Asia and Kashmir, Persian had already been introduced into the trade and administrative circles. According to Bahar-i-Gulshan-i-Kashmir, Kashmiri Pandits had acquired proficiency in Persian during the rule of Sultan Qutb-ud-Din. The Tarikh-i-Baihaqi talks of one Tilak, having studied in Kashmir and flourishing at Mahmud’s court as an interpreter of Hindi and Persian. Qutb-ud-Din built a college at his headquarters in Qutbuddinpora in Srinagar. The vicinity of the college is called Langerhatta. Sultan Qutb-ud-Din induced Syed Jamal-ud-Din Muhadith in Srinagar where he set up his institution called Urwatul Wusqa which became a famous centre for Arabic and Persian in Kashmir. The first Persian verse composed by a Kashmiri is also attributed by some chronicles to Qutub ud-Din.

Syed Ali Hamdani came to Kashmir thrice. He wrote numerous books in Persian as a guidance for the rulers and the common men. It was Hamdani, according to Allama Iqbal, who laid the foundations of “Iran-e-Sagheer” or the “Little Iran” in Kashmir. Sultan Sikander’s, under the influence of Hamadani, built a college near Jamia Masjid and his patronage for literature attracted scholars and poets from Iraq, Khurasan and Transoxiana to his court.

During the rule of Zain-ul-Abideen, Mulla Ahmad Kashmiri translated Kalhana’s Rajtarangini into Persian. He established the first translation bureau, Daar-ul-tarjama which was headed by Som Pandit, where the translators were commissioned to translate texts from various languages into Persian and Kashmiri and vice vera. He established a University at Naushehra which flourished under the able guidance of an eminent scholar, Mulla Kabir Nahvi. Sultan himself, under the ‘Nom de Plume of Qutb’ composed poetry in Persian and one of his compositions in Persian is famous as Shikayat. It was during this his time that the sweetest language of Asia found the deepest roots in the soil of Kashmir with natural beauty of Kashmir finding an exquisite expression in the Language of Iran and its vivid phraseology. There was rise of saint-poets, most notable among them being Baba Daud and Yaqub Sarfi. Sheikh Yaqub Sarfi is credited with compilations of both prose and poetry about Islamic rituals, Traditions of Prophet and various social issues. Following the general tide of rising “King poets”, Sultan Haider Shah and Hussain Shah Chak composed books of prose and poetry.

In the Malkhah graveyard in Srinagar is buried a famed poet Mazhari. He was employed by Akbar as the superintendent of waterways in Srinagar. According to Abu’l Fazl, Mazhari wrote poetry from early youth and and had travelled all the way over Iran, Khurasan and Hindustan meeting all great poets of his time. He is said to have composed over six thousand Persian couplets. One of his couplets reads:

laala tooram, na humchoon ghuncha gulboo zadaem

Shaula jae bakhya bar chaak-e-gereban meezenam

(I am the Tulip of Sinai and not the bud borne of a rose

To my torn collar, I apply the needle of my fire to stitch it)

Other famous Persian poets of this phase include Mohsin Fani, Aslam Salim, Auji Kashmiri, Filtrati, Furughi, Najmi, Sati, Muhammad Taufeeq, Habibullah Hubi, Faribi, Khawaja Rafi, Ashraf Dari, Akmal Badkashi and Tahir Ghani Ashai.

Tahir Ghani was a man of extraordinary intellect. Siraaj-ud-din Ali Khan in his Majmu-a-nafaai writes, “There are few poets comparable to Ghani in the Indian subcontinent. He excels not only his contemporaries but almost all his predecessors in many aspects.” When praising rulers was a norm, Tahir Ghani did not write even a single couplet eulogising rulers. He chose social and moral themes unlike other Persian poets of his era.

Iqbal, in his Payam-e-Mashriq, praises Ghani and calls him “the nightingale of poetry who sang in the Kashmir’s paradisal land”.

Saadat Hassan Manto mentions Ghani in his letter addressed to Jawaharlal Nehru. Manto also mentions an incident where a famous Iranian poet deliberately leaves his diary with an incomplete couplet in Ghani’s empty house, so that he would complete it once he was back.

Ghani Kashmiri’s Divan consists of ghazals, rubaiyats and qasidas, a collection of over 100,000 couplets. A poem entitled Jangnama describing war between Aurangzeb and Dara Shukuh is attributed to Ghani in Catalogue of manuscripts in Library of the University of Bombay.

During the Mughal period when Urdu was struggling to become the court language of India, Persian had beautifully intermingled with the local literary sentiment and polished itself as the language of the ruling and the literate.

Abdul Wahab Sha’iq versified the history of Kashmir into 60,000 couplets. Sha’iq was a resident of Srinagar and when Raja Sukh Jiwan Mal called to compose Shahnama-e-Kashmir, on 1 rupee per couplet Sha’iq incorporated Firdausi’s style in his composition of the Shahnama.

Khawaja Hasan Shi’ri is said to have migrated to Delhi where he had a poetical contest with Ghalib. He was bestowed the title Fakhr-ush-Shura Aftab-i-Hind by the Sultan of Turkey for whom he had composed a Qasida.

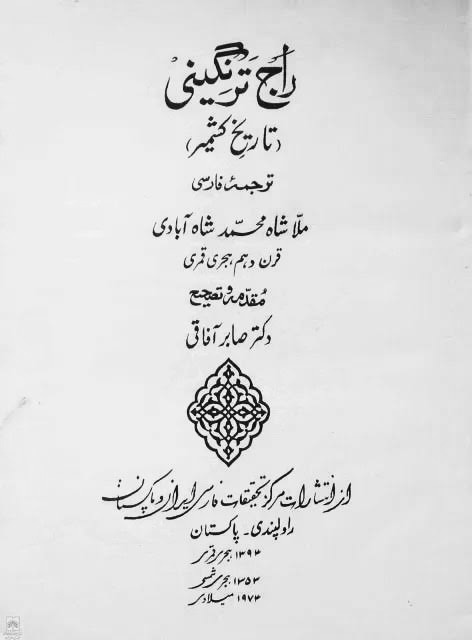

Of an equal importance are the various hagiographical works written in Persian. The earliest such work written in Kashmir is probably Mullah Aḥmad’s Bahr al-asmar. Important chronicles are Badehra’s Rajdarshani, Khwaja Aẓim Deda Meri’s Ketab-e tarkh-e Kashmir, Ghulam Nabi Khanyari’s Wajiz al-tawāriḵ, Ḥaji Moḥi-u-Din Meskin’s Tarikh-e kabir-e Kashmir, anonymous Baharestan-e-shahi .

Pir Hassan Shah’s three-volume history: Ghulistan-e-Akhlaq, Kharat-e-Asrar and Ijazi Gharibi, Syed Ali’s Tariki-e-Kashmir; Tarikh by Malik Hassan Chaudury; Tariki-e-Kashmir by Narayan Koul Ajiz.

Persian as a fault-line between the elite and the poor

While the Persian continued to flourish as the language of the learned, the poor peasantry of Kashmir mostly kept themselves aloof from it. The Kashmiri poetry and literature, unlike the Persian, found its roots in folk songs and ballads. The peasant would put in words his emotions when his herd wound over the pastures, he would sing to the flocks of sheep, he would talk about the harvest- the surplus, the scarcity, the famine while rhythmically pondering over the deeply ingrained tradition of mysticism intricate to the meadows and mountains of the countryside .

A notable folk poet, Sabir Tilwony in one of his poems titled “Yarqand anoan zeinaan”, sings of the valour of Kashmiri labourers who participated in the construction of Gilgit Road under Begar system. The poem presents abject surrender to the rulers and an unquestionable worship of tyranny that the gullible peasants had to endure. Maqbool Kralwari’s “mathnavi gries naamah” gives insight into the prevalent socio-political conditions of his time. In this social satire, Maqbool goes onto criticise the clergy for looting ignorant peasantry and extorting money from them by keeping them submerged in the mire of superstition. Kralwari employed local tirades, proverbs and even cuss words and abuses to convey to the reader the nervous urgency with which he wanted to address the predicament of the labourers.

The Kashmiri ballads reverberated the very life of Kashmir, harnessing local language to present the poetry of truth. While Persian literature in Kashmir depicts the aesthetic finesse of the well read, Kashmiri literature enshrined the Kashmiri home traditions and ingenuous emotions in a poetic metre. Kashmiri poets composed mysticism and romance but the influence of poverty and class based tyranny would always touch upon their renditions, overtly or covertly.

Persian and power:

With Persian becoming the court language, a new breed of functionaries was brought to fore who chose Persian over Kashmiri and Sanskrit to stay in the echelons of power. Even though there were mass conversions in Kashmir, and contrary to the popular belief, it were the Kashmiri Brahmans and a few elite Muslims who became the epicentre of administration under various Muslim rulers, by learning the new language; a complete opposite of the rest of the subcontinent.

According to Professor Ashraf Wani:

Though Islam became the court religion in 1343 C.E. after Shahmir ascended the throne, the administration continued to be in the hands of the traditional class—the Brahmans.

The influence of pandits became most prominent during the time of Zain-ul-Abideen when they were in-charge of land settlements and agriculture. During the Chak rule, Brahmans continued to serve in the administration. While we hardly find any Kashmiri Muslim notable mentioned in the Mughal history of Kashmir, there are references to many a Kashmiri Brahmans such as Tota Ram, Miru Pandit, Bulaqi Pandit, Makund Pandit, Pandit Mahadeo, Mahesh Shankar Das and Mukund Ram Khar serving the Mughals at positions of influence. Even during the rule of Aurangzeb, Brahmans continued to man the affairs of state and rose to prominence largely because of their proficiency in Persian. During the brutal Afghan rule, Pandit Nand Ram Tiku became prime minister of Kabul, and his name appeared on coins issued from there. Pandit families such as the Dhars, Kouls, Tikkus and Saprus constantly appeared in public service.

Hence, Persian in addition to being the “sweetest language of Central Asia” became a tool of influence that would go on to determine centuries of political struggle and power dynamics…

In 1889, Dogra rulers adopted Urdu as the language of administration.

Leave a comment