The British had no legal and moral rights to transfer the hereditary and proprietary rights of Kashmiris to the Dogra rulers. The deal was one of the worst sales of peoples in the world by the imperialists, in the garb of ‘treaties’, the darkest side of the deed being the unfortunate sealing of moral and existential fate of millions of indigenous who, along with their land, were traded like cattle to the British vestiges.

The treaty, executed on 16 March, 1846 stated that Gulab Singh acquired “all the hilly or mountainous country with its dependencies situated to the eastward of the River Indus and the westward of the River Ravi including Chamba and excluding Lahul, being part of the territories ceded to the British Government by the Lahore State according to the provisions of Article IV of the Treaty of Lahore, dated 9 March, 1846.

Under Article 3, Gulab Singh was to pay 75 lakhs (7.5 million) of Nanak Shahi rupees (around 63-68 Lakhs East India Rupees) to the British Government, along with other annual tributes. The Dogra rulers tried to extract this sum form the people of the land in form of heavy taxations on local produce, arts and crafts.

During the rule of the Maharajas (1846-1947) everything, save air and water was taxed. Robert Thrope and Walter Lawrence have provided us with information on taxes which included the ones on birth, circumcision, marriage and tax on birth of calves, cattle and foul.

However, one of the most grotesque sides of the exploitation was institutionalisation of prostitution in Kashmir.

Prostitution had existed in Kashmir since ancient past. Kalhana, in his Rajtaranghni, had censured some of the kings like Kalasha, Kshemagupta, Uccala and Marsha for patronising prostitutes, paramours and courtesans.

It was Sultan Sikander who is reported to have banned prostitution in his sultanate.

The Afghan period in Kashmir which started in 1753 was the worst period in this regard. Amir Khan Jawan Sher, the Afghan Governor, first institutionalised this trade and all those involved in the trade were registered. Kashmiri slaves, both women and men were exported to Kabul.

However, flesh trade took monstrous shape during the Dogra rule. In 1880, Maharaja received 15-25 per cent of whole revenue of the State from “licensed” prostitutes. It is said that there were 18,715 “State prostitutes” in Kashmir in 1880. Trade in women was part of the state machinery to eke out taxes from the people. The general poverty of the masses and the burden of taxation on the poor peasants gave a great boost to the trade. Kashmiri Pandits and high caste Muslims (Pirzadas) kept away from prostitution. However, for the poor people, this was a lucrative profession. This was eased by the Dogra rulers by giving the brothels a legal sanction. For the rulers, the money procured from the sale of licenses and the work of registered prostitutes acted as an incentive to keep the trade running .

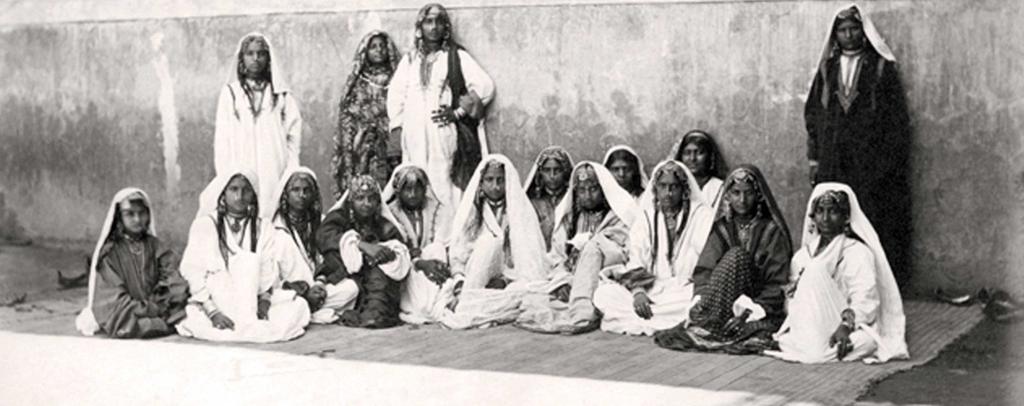

The prostitutes were divided into three classes/tax slabs according to what the records term as “gratification,” which included considerations of age, income, looks and caste of the prostitutes. These three classes were referred to as 1st, 2nd and 3rd class prostitutes. 1st class prostitutes had to pay a tax of Rupees forty, 2nd class prostitutes Rupees twenty and 3rd class prostitutes Rupees ten per annum to the state. On an average, before the famine of 1877–78, of a total taxation amount of seventy to eighty thousand rupees from all professions, prostitution contributed a sum of Rupees fourteen thousand.

Prostitutes were mostly destitute women, victims of domestic violence, or those deluded into a prospect of matrimony. The records name these women as “human chattels.” Some of them were sold for cash, and some others were given in marriage to people unable to find wives locally because of the inequality in the ratio of males to females. The province of Punjab was a large buyer of women and depended principally upon Kashmir. This was because of the skewed ratio in the number of males to females in Punjab, given the son preference in the region

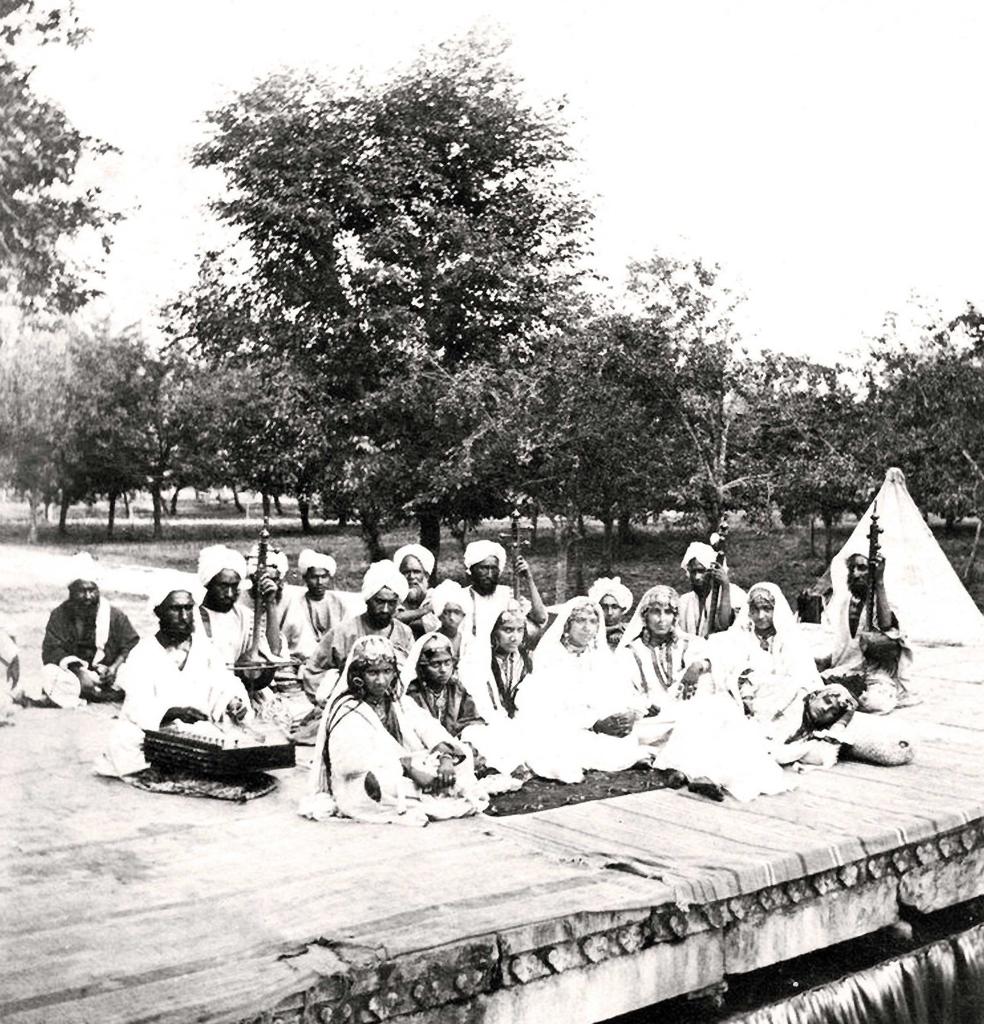

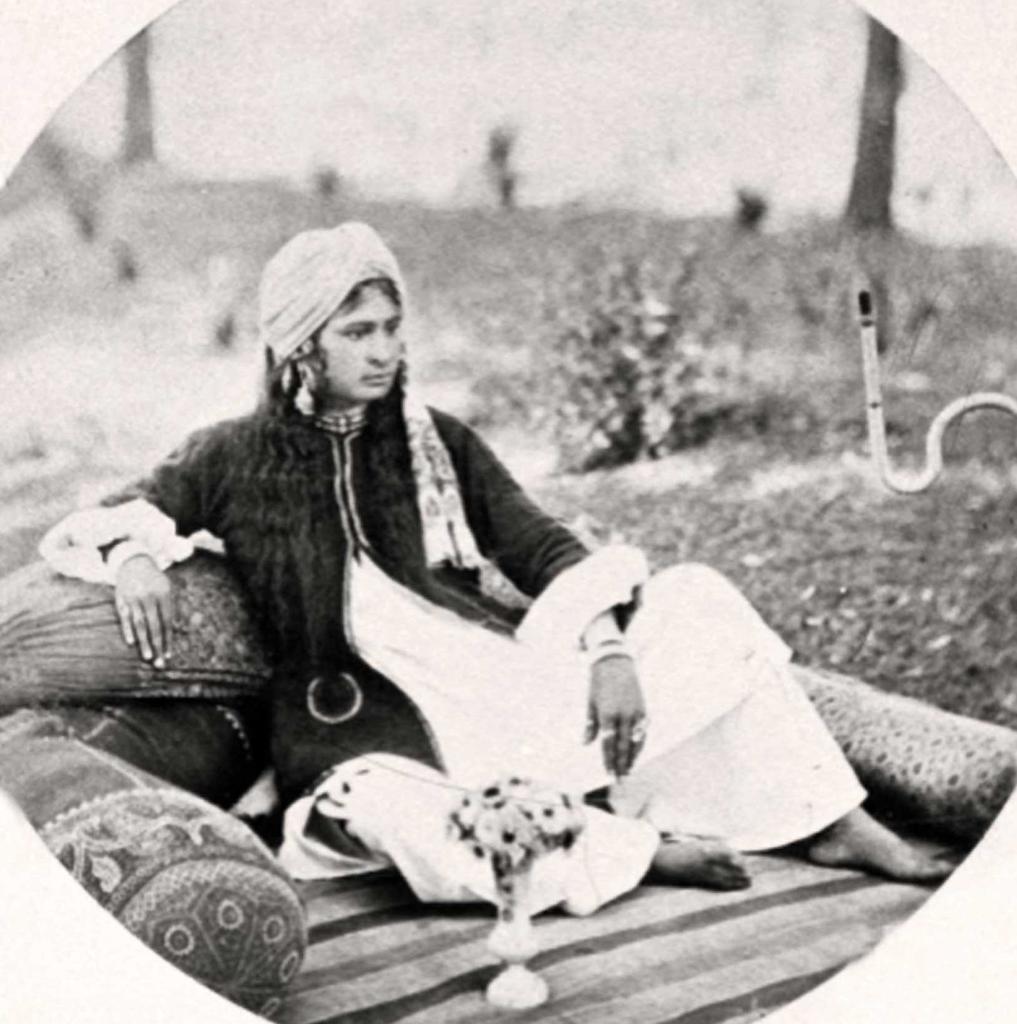

These girls initially started as dancers and were given a respectable name of “Hafiza” but with passage of time and heavy taxes imposed by the authorities they were forced into selling their bodies and relegated by the word Gaani (prostitutes).

The sale of young Muslim girls in Kashmir to the established houses of ill-fame was both protected and encouraged by the state, as it was highly beneficial to the exchequer. All Hafizas had to pay a hefty registration fee of 200 chilkee rupees per year plus half of their total earnings which amounted to almost one fourth of the total yearly revenue of the state in form of the much sought after ‘Kanjur Tax’.

In 1867, Arthur Brinkman, in his work – The wrongs of Cashmere, indicted the government of Maharaja for patronising prostitution in Kashmir.

Arthur Brinkman writes: “The classes engaged in it [prostitution] are owned as slaves and others, who were formerly in their position. The authority of the latter is backed by the whole power of the Dogra Maharaja, to whom reverts at their death all the wealth gathered by the prostitutes, during their infamous life. Should one of their bondwomen or dancing girl attempt to leave her degraded profession, she is driven back with the lash and rod into her mistress’s power. These facts are certain“

According to Robert Thorpe, during Ranbir Singh’s time the license granting permission for purchase of girls for this purpose cost about a 100 chilkee rupees. Robert Thorpe wrote further that the Kashmiri girls were being forced into prostitution by the authorities with the idea of earning more and more revenue from licensing the flesh trade. The traveller lamented that such sales took place because people were poor, and the poorest among them sold their children.

With the licensing of prostitution, certain unscrupulous elements found the job profitable which assumed a shape of business venture for them. They came to be known as ‘Kanjar’ or ‘Dalle’ and worked as agents for supply of girls for the red lights areas outside Kashmir, such as Quetta, Peshawar, Lahore, Delhi, Lucknow and Calcutta.

Kashmiri girls were in demand in the brothels of Agra, Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi, Hyderabad, Lahore, and Punjab, “owing to their fair skin and comely looks.” According to one official record, the modus operandi of people engaged in the trade was that: After making “business connection” down country and insuring a ready market there, these traders in women periodically visit the State to collect the “goods” already procured or earmarked by their local agents who are mostly brothel-keepers, pimps and others in the same profession; or go roaming around places where, according to their information, there are reasonable prospects of picking up women “cheap and easy.” In a large majority of cases, the victims, it would appear, fall willingly into the snare laid out for them. In some cases they are the victims of artifice or deception. Force is seldom used .

The archival records state that some of the hotels and restaurants in Srinagar that held a bar license engaged barmaids to lure customers, which was seen to have encouraged licentiousness. The officials of the time believed that “All the women employed at the cafes are with rare exception, women of loose character. The proprietors of the cafes employ them only to lure customers.”

These cafes are defined in the records as being “brothels of a refined type” although what it meant is not clear. To prove that barmaids were used to entice customers, an example was provided of an Iranian girl, Ewan Taj Khan, who it was argued did not know the language of the common people and as such was unfit to be a barmaid. It was further added that the sooner this “pernicious practice” was stopped, the less chance there was of the moral of the people being corrupted . In the year 1939, three hotels had bar licenses in Srinagar– Standard hotel, The New Cafe and Wahid hotel. Most of them were situated amidst the thick population and some even had branches in houseboats. Through the “activities” of barmaids in these hotels, some of whom were called from Lahore as well e.g., Mrs. Williams and Miss Durris, the police had concluded that the liquor shops in these hotels were usually the abode of “undesirable persons” to whom liquor was being sold at unusual times.

In Srinagar city, the red light areas of Maisuma, Gawakadal and Tashwan became prominent. Under directions of the British, after the devastating famine of 1877-78 the Maharaja’s government conducted a survey in 1880 revealed that there were about 18,715 licensed prostitutes involved in flesh trade in the valley.

The sexual exploitation of the Kashmiri Muslim girls as Hafizas and Gaanis added a fortune to State exchequer, but no money was spent on their benefit. Mr. Henvey, officer on special duty on Kashmir in 1880, writes that no care was taken of the sick prostitutes. A survey made by the Church Mission Society in Srinagar, revealed that during the years 1877 to 1879, the total number of patients treated in the Mission Hospital were about 12,977 cases and 2,516 out of them had venereal diseases. The syphilitic disease was spreading like wild fire throughout Kashmir.

To further legalise the flesh trade, Dogra Durbar passed “Public Prostitutes Registration Rules” in 1921. The rules introduced the term “Public Prostitute” and defined it as, “woman who earns her livelihood by offering her person to lewdness for hire.” It ordered that, “Every public prostitute starting or carrying on or continuing business as such public prostitute, within the limits of any place where these rules are in force shall, in the manner herein provided have her name entered in the register kept at such place and obtain a certificate of registration”.

A register of public prostitutes would be kept in the office of the Deputy Commissioner or other public servant empowered in this behalf by the Minister-in-charge of Municipalities.

Any woman seeking the office for registration had to write an application stating her name, age, parentage residence and verified by the applicant “in the manner provided for signing and verifying the plaints by the Code of Civil Procedure”.

The application would be accompanied by a payment of Rs. 5 (in comparison to greater amount previously) as registration fee. These rules further introduced the term “Brothel keeper” and defined it “as occupier of any house, room, tent, boat, or place resorted to by person of both sexes for the purpose of committing sexual immorality and every person managing or assisting in the management of any such house, room, tent, boat or place.”

The fourth Dogra ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh ascended the throne in 1925 and was seen by some as “modern and emancipated” when compared to his predecessors. He encouraged compulsory education among the masses and introduced some reforms in taxation but he too did not abolish the prostitution tax and the flesh trade kept on thriving as usual during his rule.

The year 1931 usually marks as a watershed in the struggle of Kashmiris against the Dogra rulers and is characterised by massive political upheaval and mobilisation by the Muslim peasants under young Kashmiri leaders who had returned from outside Kashmir, equipped with the advanced western education.

However, none of these leaders raised a voice against the flesh trade. Neither did plight of the innocent young girls engage attention of the leaders of the religious reform movements.

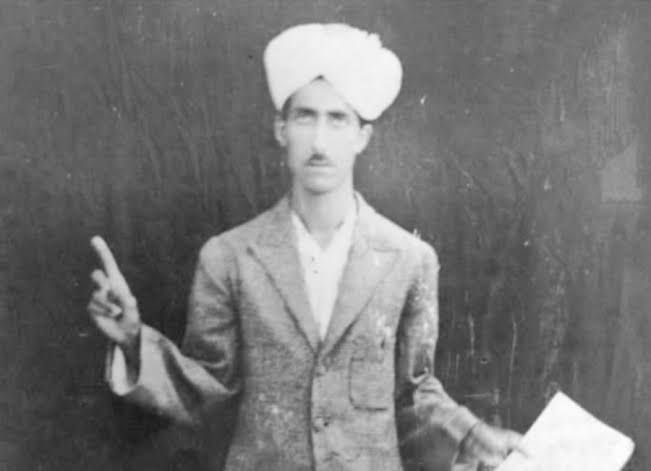

It was a gallant barber from Srinagar by the name of Mohmammad Subhan Hajam who went on a crusade against the flesh trade in Kashmir. Subhan owned Prince hair-cutting salon near present day Lal-Chowk, Srinagar. Despite his meagre income and frail physique, he was equipped with great moral courage to face all challenges.

Tyndale Biscoe mentions in his autobiography that, Subhan who lived in Maisuma, “was continually disturbed at night by ribald songs accompanied by musical instruments such as harp and zither, and also by men wrangling” but what upset him the most according to Biscoe were, “the cries of anguish from the unfortunates recently forced into a cruel life, many of them quite young, who had been sold by their relations under the pretence that marriages had been arranged for them”.

Subhan Hajam popularly know as Subhan Naed (Subhan the barber) wrote pamphlets to expose this cruel traffic and distributed hundreds of them in the city. He and his friend would stand in the streets preaching against the vile trade and at night they would stand outside brothels to prevent men from entering them. He composed poems in Kashmiri and Urdu, against prostitution and those who endorsed it.

It was in the year 1924, when Subhan was only 14 years old, that he took out his first pamphlet against prostitution in which he wrote against Maharaja’s officials and brothel keepers. In one of his pamphlets titled Hajam ki Fariyad (Appeal of a Barber), Subhan lamented that the state was not cooperating with him and some vested elements were creating problems.

In particular, his powerful poems against prostitution, Hidayatnamas (Directives/Guidelines), published in the local press, are an indicator of how much he detested the practice.In his verses, he hurled insults and taunts at the pimps. In his poetic compositions, he exhorted the people to remain away from the brothels and called on the ruler to ban the menace. Subhan would also meet the influential people and members of civil society and seek their support in raising awareness about the issue and assistance in the fight against it.

He writes:

Oh, Subhan!

Be careful

You have to take care of the fallen

You have to remember Prophet

Muhammad For god’s sake beware

Subhan, through these poems, evokes horrifying images of life after death, doomsday, and hell to persuade prostitutes to denounce prostitution. About the religious prohibition on the last rites of prostitutes, he writes:

This is the decree of religion

Do not offer funeral of a whore

Everyone has an opinion on this

For god’s sake beware This is the decree of religion

Don’t provide a whore cemetery

Obey this every time

For god’s sake beware

Envisioning the doomsday and hell, he writes:

For god’s sake

just forget Bad deeds from your heart

The doomsday is very scary

For god’s sake beware

When you will go to hell

Then you will remember the creator

You will be welcomed by fire

For god’s sake beware

Due to his persuasion, 700 people including Kashmiri Muslims, Pandits and Sikhs supported him and submitted a memorandum to the District Magistrate in Srinagar seeking a ban on prostitution.

Subhan Hajam was attacked several times by the pimps and goons employed by keepers of the prostitution dens. In order to suppress his voice, several false cases were filed against him in the courts of Srinagar. All these attacks on him were spearheaded by a rich and influential red-light area chief known contemptuously as Khazir gaan. He would corrupt police officers to seek vengeance on Mohammad Subhan Hajam.

All these intimidating attacks did not succeed to bow down Subhan’s crusade, who had now succeeded in winning the hearts of all sections of the society – Muslims, Pandits and Sikhs alike. He even received support from the Church Mission Society and Rev Tyndale Biscoe, the doyenne of education in Kashmir.

Subhan Hajam pleaded not guilty in all cases filed by the police against him. Pandit Bishember Nath – the city judge, exonerated him honourably from all the charges.

It was Molvi Mohammad Abdullah Vakil, who on behalf of Subhan Hajam, raised the issue in the Praja Sabha in 1934 and proposed exacting a law for the closure of prostitution houses in the Kashmir.

Soon the members of political parties started raising voices again the flesh trade. Even the Viceroy of India asked the Maharaja to provide him detailed information about the flesh trade in Kashmir.

Due to this intense public pressure, the State assembly passed “The Supression of Immoral Trafficking Act in 1934”. The assembly ordered deputation of two Police officers to find and repatriate Kashmiri girls from the red light areas of Rawalpindi, Lahore, Peshawar, Quetta, Delhi and Lucknow.

A police officer Abdul Karim recovered a large number of such unfortunate girls. Fines were imposed on people who clandestinely operated brothels.

Most of the Hafizas took to Charkha (handloom) while some other were absorbed in silk factory Srinagar.

The conditions and occupations of women furnish a subject of intellectual interest and discussions among the academia because they are reflections of the larger moral, social and economical fibre and working of a political structure. The pathetic conditions in which the Kashmiri women languished during the kingship directly represent the utter mismanagement and mal-governance that Kashmir had plummeted into, leaving the poor peasant penniless and the women clothless.

Leave a comment